‘The Path’ by artist Hassan Hajjaj opened at the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol on 30 July 2020. As writer in residence at the Arnolfini, Melissa Chemam was invited to organise a Zoom conversation with Hajjaj, and had the pleasure to meet him soon after in the gallery during the installation.

Born in Morocco, raised in London, Hassan Hajjaj is no stranger to Bristol. In the 1980s he was heavily involved in sound system clashes with DJs from Bristol, like the Wild Bunch. He befriended some of their members: Nellee Hooper (who a few years later joined Jazzie B and the band Soul II Soul), and Daddy G (who soon participated in founding the unconventional music collective Massive Attack). Hajjaj has long been a fan of Roni Size’s drum’n’bass sound, which emerged in Bristol and London in the mid-1990s.

Music – and in particular that type of underground, DIY electronic music – has always been part of Hajjaj’s world and work.

“Our immigrant neighbourhood as kids, in East London, became my melting pot,” Hajjaj told me. “My training happened in the streets more than anywhere else, among friends. We didn’t have much places to hang out, so we just met in the corner of our parents’ place! But we were all driven by our desire to be a part of this London scene. We wouldn’t go to university. Later, one became a cook, another friend a video maker, another a fashion designer, many others worked in music.” And Hassan was always contributing.

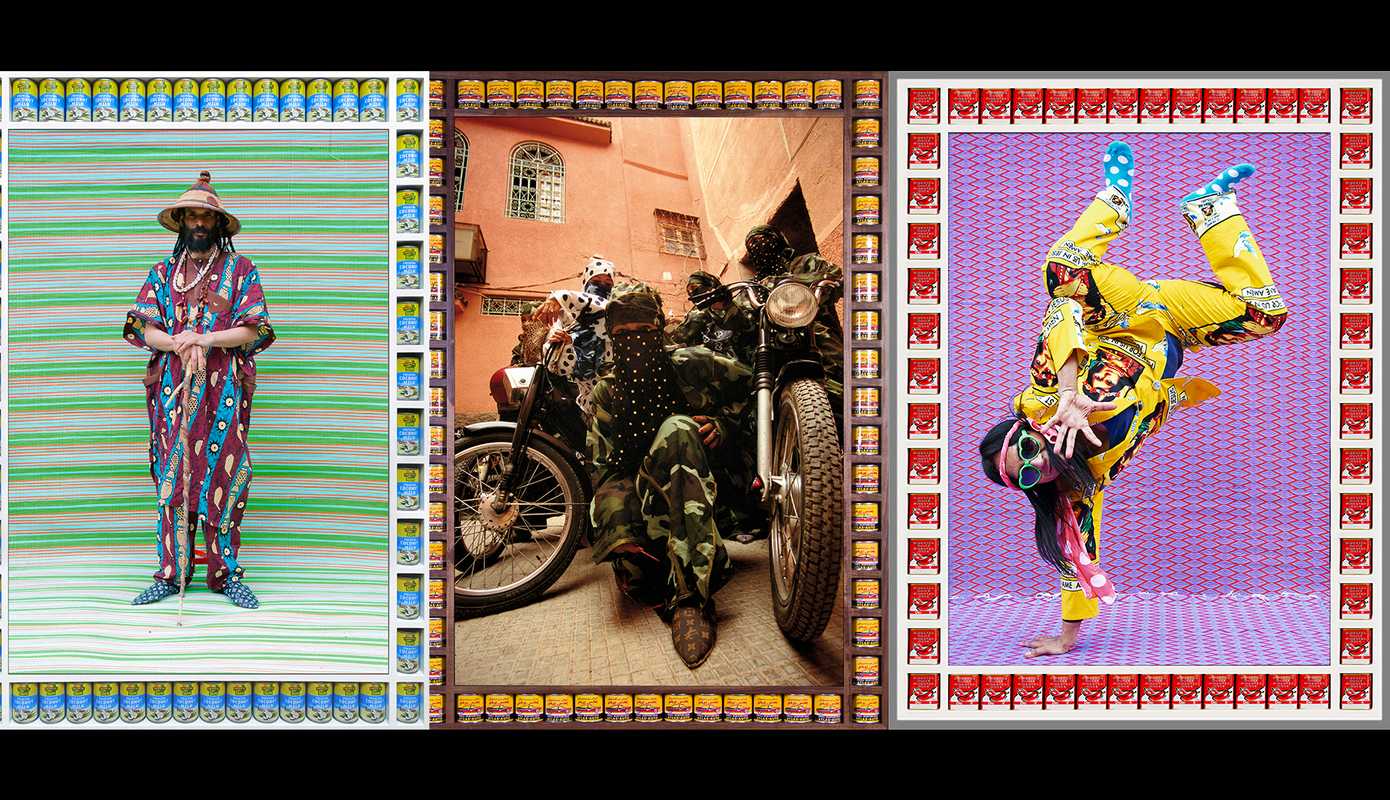

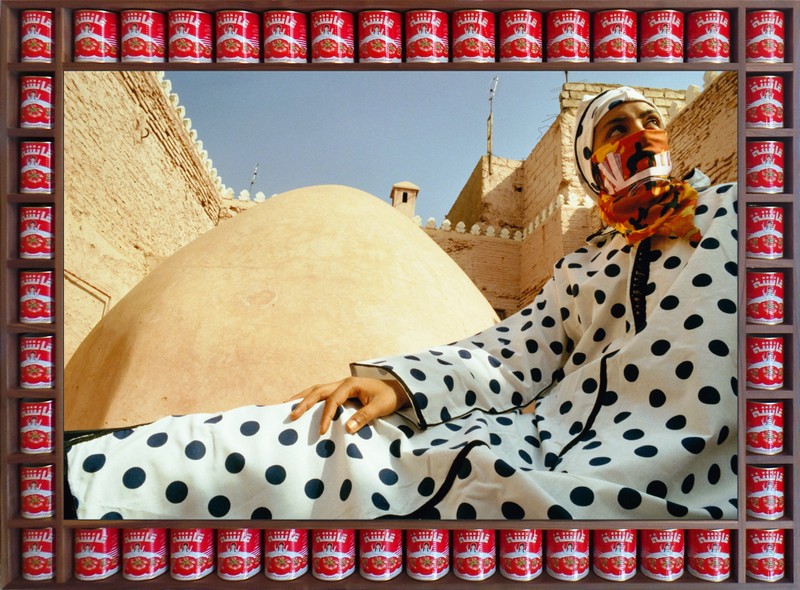

Since the late 1990s, his film and photography work has been inspired by London’s immigrant cultures. It has now toured the world, graced the covers of the likes of Vogue, and Hajjaj has worked with Billie Eilish and fellow Moroccan singer Hindi Zahra. As a result, Hajjaj’s work is an invitation to a clashing voyage, full of unexpected encounters, vibrant colours and patterns.

‘The Path’ is a timely exploration of global culture across continents through the unique lens of the acclaimed photographer, confronting his dual-identity. It references his personal journey from his birthplace in Larache, Morocco, to London, and now beyond, through his experience working around the world.

“I first grew up in Morocco, a world in technicolour compared to England,” Hajjaj added, “and when I arrived in London at the age of 13 I felt like I had landed in a film noir.”

In East London, Hajjaj’s crowd was full of Jamaican, Pakistani, Indian, Bangladeshi, African young people, though he was the only Moroccan. Their arts didn’t come from galleries but from radio and television, infused with a love of reggae and hip-hop.

“I was documenting our otherness, I think,” Hajjaj said. “That’s why there is colour in my work, addressing religion a bit, and a touch of politics. You know, I left school at 15, with no qualifications. My friends and I were too uncomfortable to go to a museum or a gallery, a world far away from us. So as a group of creative people we just nourished each other. I used to programme the parties, I would find the DJs, etc. And had a small boutique for street wear called RAP that became a meeting point for us, and for other untrained artists.” There is something in Hajjaj’s work that permanently defies the rules of academic art, constantly redefines what beauty is and how humour can meet glamour. His photographs, in a museum, feel like bold statements. They were however exhibited in the prestigious Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris in 2019. Unlike most Morrocan immigrés, Hajjaj’s parents didn’t move to France, Morocco’s former coloniser. What made him truly confident in his original gaze was the melting pot of Shoreditch and later on Camden.

‘The Path’ represents the two parts of Hajjaj’s journey, in Morocco then London. It includes a collection of portraits and scenes representing women in Muslim dresses, their faces covered by bright and playful veils or hijabs, plus portraits of African artists. These images stand out in our weird year 2020, its abnormality, showing how masks and social distance could actually be, in another culture, the norm, and how black artists could take centre stage.

The exhibition aims to celebrate Black culture. In the second part of the show, we see portraits of African musicians wearing clothes designed by Hajjaj that reference modern African patterns and habits, in bright yellow, purple and green. Among them are Boubacar Kafando, Mandisa Dumezweni, Luzmira Zerpa. Titled ‘My Rock Stars’, the portraits shine with energy and joy. In the last room, the visuals suddenly animate when the photos become short films, in which each of the photographed artists interpret a song a cappella or with their own African instrument .

“The title comes from the name of one of my favourite albums, The Path by Ralph MacDonald, which recreated the history of African music up to jazz,” Hajjaj explained. “It’s both the story of my journey from North Africa, and the journey of all the newcomers I grew up with.”

While Bristol is still in the midst of boiling debate after the removal of Edward Colston’s statue, a slave trader from the 17th century long celebrated as the main local benefactor of the city, Hajjaj’s set of daring images stuns in response to the narrow-mindedness that led to Colston’s white-washed ‘benevolent philanthropist’ status in the first place. That same white-supremacist attitude also recently led small groups to organise protests asking for the statue to be brought back to its plinth.

Bristol people, curators, writers and artists, are indeed still debating weekly the urgent need to decolonise museums and art galleries, to truly confront colonial history and to give more space to immigrant artists and creatives representing other cultures. But many others are more concerned by the growing number of foreigners, or simply outsiders, overshadowing the rights of the “native Bristolians”. Yet ‘The Path’, with its explosion of colours and liveliness, is a welcome celebration of joy, DIY ethos, optimism and togetherness, in times of crisis and distancing – just like Bristol’s groundbreaking culture was in the 1980s, with the emergence of a bursting graffiti scene, vibrant reggae-infused sound systems and a new sound that was later embodied in Massive Attack’s first album Blue Lines in 1991. Fittingly, these young artists were exhibited for the first time at the Arnolfini in 1985, in the exhibition Graffiti Art, where the likes of Goldie and New York graffiti artists Brim and Bio joined the party led by the Wild Bunch. ‘The Path’ is part of a multicultural journey that is still ongoing.

‘The Path’ by artist Hassan Hajjaj opened at the Arnolfini Gallery in Bristol on 30 July 2020, after a first iteration at New Art Exchange, Nottingham, as a touring exhibition curated by Ekow Eshun. The artist also has a show in South Korea, ‘A Taste of Things to Come’, which opened on 5 August at the Barakat Contemporary Gallery in Seoul.