Warning: This piece contains spoilers.

There’s a moment early in Nickel Boys, RaMell Ross’ Best Picture-nominated feature film about an abusive mid-century American “reform school”, that replays in my mind. The protagonist, Elwood, is in a restaurant, and two Black women walk back and forth from a lunch counter, one after the other, in oppositional symmetry.

The film, which is adapted from the Colson Whitehead novel of the same name, is shot in first person point-of-view. As a result, most of the narrative is experienced through Elwood’s eyes, so we watch as he does. Our view is tilted downward – we don’t see beyond the calf-grazing hems of their Sunday’s-best dresses. But the focus and rhythm of the shot – the choreography and elegance of their bright heeled pumps against the white tiled floor – reveals Elwood’s own conception of beauty. How he looks is just as important as what he’s looking at.

Most of the narrative is experienced through Elwood’s eyes, so we watch as he does. How he looks is just as important as what he’s looking at.

Elwood is a young Black man of promise and potential, growing up in the 1960s Jim Crow South at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Painfully aware of white supremacist hegemony, Elwood has been brought up to recognise and reject its fallacies. He grew up in a loving and respectable community – think shining shoes and smart shirts – with adults who both saw and nurtured the best in him. His grandmother is his sole caretaker, and an unbelievably doting one. She uplifts him constantly, only deterring him from fully engaging in the politics of the time for fear of his safety.

His school teacher pushes him to aim high. “Imagine a textbook with nothing to cross out,” he posits, handing Elwood a leaflet for a historically black college with a tuition-free accelerated study program. A top student and avid learner, Elwood gets into the program. He is on his way to his new school when a Black man in a souped-up car slows down and offers him a ride. That car turns out to be stolen, and Elwood, though innocent, is charged as the driver’s accomplice.

In sharing Elwood’s gaze, we share his process of meaning-making. And throughout the film, I felt myself becoming increasingly aware of how little control I had behind his eyes. I leant into the tenderness of his grandmother playfully unfurling sheets around him. I tensed as he lingered on the gaudy rings of the man offering him a fateful ride.

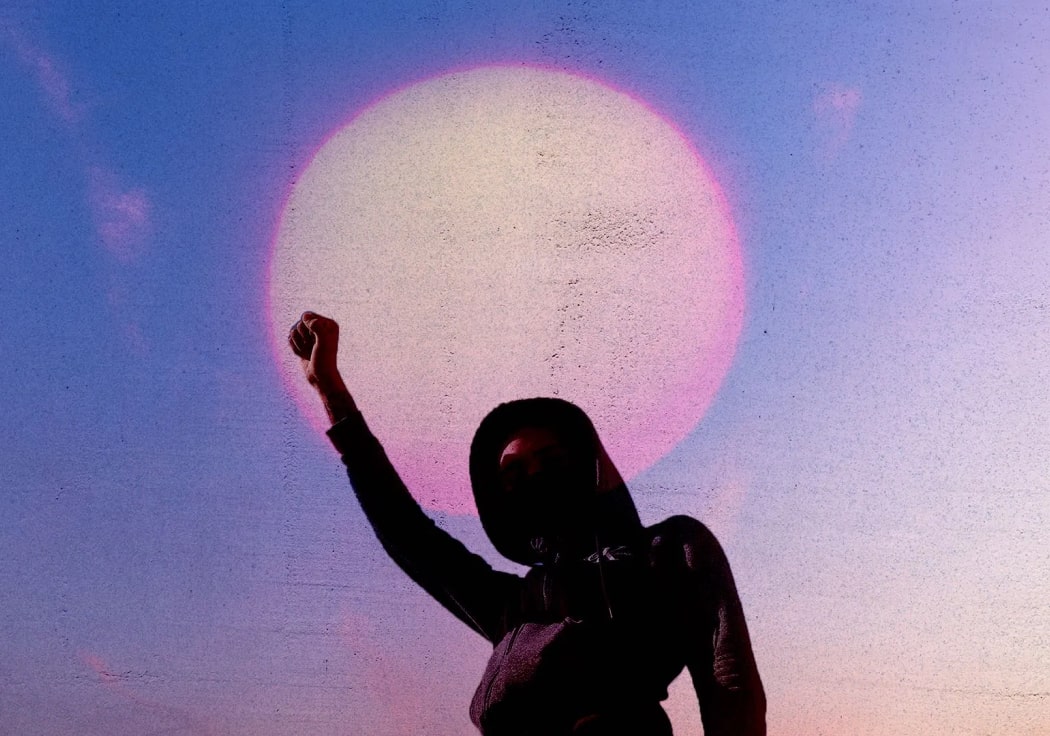

Behind Elwood’s eyes, I could not ignore the space – sometimes playful, often dangerous, always political – between looking and being looked upon. There is power in both, but perception does not exist in a vacuum. Ultimately, Elwood is a Black boy growing up in the American South, and whiteness is its inescapable, organising principle.

Elwood meets Turner at the Nickel School for Boys, a “reform school” for delinquents modelled after the (very real) Dozier School for Boys, also known as the Florida School for Boys. Dozier operated in Florida from 1900 to 2011, and gave rise to the abuse, torture and deaths of many boys who lived there. At the fictional Nickel School, white boys live in separate quarters and experience humanising, summer camp-like conditions. Black pupils learn that their daily lives will be marked by neglect, physical and mental abuse, and an impossible standard for “graduation”, at which point they may leave.

“I knew my mama loved me, she just loved to drink more,” Turner tells Elwood. He talks about getting between his aunt and the fist of her abusive boyfriend, painting, if sparsely, a picture of a life marred by violence, racism and poverty. The two quickly grow close and their opposing outlooks on their condition becomes clear. Elwood knows he does not deserve to be there, and does not want to normalise the way the school dehumanises him and his Black cohort. Turner is resigned to his fate, and more interested in navigating the space in a way that brings him the most ease. Neither is wrong – their differing perspectives are a symptom of the lives they have lived.

But there is a significance to how Elwood looks at Turner. At first, it feels nostalgic. The lens makes his edges soft, his smile sweet, and gives him doe-like eyes that had me certain he would be the one to die. It felt like we were seeing the best and most beautiful of him as remembrance.

Scenes of a grown-up Elwood on the outside, always shot from behind, bolstered that belief. Grown-up Elwood sits at his computer researching reports on unmarked graves found on Nickel’s grounds, and decades of abuse at the school he managed to escape. In the first of these scenes, I breathed a painful sigh of relief that Elwood made it, even if the act of now watching him from behind – and not through Turner’s eyes – felt foreboding.

How your people see you is important. More often than not, it is how we learn to see ourselves. Elwood can see himself as worth more than what Nickel, as a microcosm of American racism, has allotted him. The loving lens of Elwood’s upbringing allows him to question and reject the abuse meted upon Black boys at Nickel. But part of the devastation of Nickel Boys is the reality that, ultimately, his foundational love and innate sense of worth isn’t enough to save him. Not from the gaze of the white officer that stops the car, or the whip of his white teacher who can only see a creature in need of taming, or the cocked gun of his ex-workmate – a blurry white figure who’s the last image we see from Elwood’s view.

How your people see you is important. More often than not, it is how we learn to see ourselves.

But how Elwood sees Turner is enough to save Turner. It is because of Elwood’s plan to share his documentation of abuse that Turner resolves to escape. “They’re going to kill you,” Turner says to his friend, near-lifeless after hours of torture in an airless sweatbox. Without Elwood’s dogged belief in justice, the two would have never left. Though Elwood got caught, Turner got free.

There is both trust in and care for the viewer in Ross’ directorial choices. Nickel Boys does not linger in brutality to have its tragedy felt. I think of other explorations of American racial violence that use “point-of-view” techniques, like Barry Jenkins’ screen adaptation of Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad. I saw it when it first came out and was floored by Jenkins’ virtuosity throughout the series, but also felt embodied terror when watching its visceral portrayals of Black death through point-of-view shots. Nickel Boys is telling a different – though related – story of racial capitalism through the Black gaze, and I appreciate the space Ross leaves for us to tell it with him.

Neither Turner nor Elwood should have been at Nickel. But this was, and is, the United States of America. As bleak as the predicament for both boys was, I don’t believe the goal of Nickel Boys is for us to drown in pessimism. I sat through the credits with a tear-stained face, grateful for the film’s aching beauty and unflinching allegiance to truth.

The telling of this story, and handling of Black death, is enhanced by Ross’ background in documentary, and his use of archival material in the final montage feels rigorous, expansive, and so artful. From faded images of young boys, to time-lapse clips of MRI brain scans; to grainy videos of Apollo 8; to the multiplying of embryonic cells – there is space to consider what it means to be human, both in concept and context.

Ross is an auteur, and what a gift it was to watch his feature debut. Still, the experience was as painful as it was beautiful, so from here on, my time with Nickel Boys may have to remain a memory.

- Nkenna A Ibeakanma is an Igbo writer-performer from London.

.png)