This summer, a storm gathered over the literary world. Campaigners within the books industry called attention to Baillie Gifford, an Edinburgh-based investment management firm whose cultural sponsorships have long been shadowed by its ties to fossil fuels and companies linked to the Israeli occupation, apartheid and genocide. Over the past two decades, Baillie Gifford has been a prominent patron, funding literary festivals such as the Edinburgh International Book Festival, Hay, Cheltenham, Stratford, Henley, and Borders.

The goal of the authors and campaigners, who also organise under the name Fossil Free Books, was simple: get Baillie Gifford to confront and stop their complicity in environmental destruction and human rights abuses. Pressuring the literary industry to examine its ties with harmful funding sources was part of the strategy. When both Edinburgh and Hay – respected festivals with considerable influence in the publishing industry – announced in May that they were cutting ties under mounting pressure; it felt like a victory for those calling for accountability. But in a move that felt like retaliation, Baillie Gifford abruptly withdrew funding from the other festivals it was supporting, and the mood shifted dramatically.

This withdrawal of money exposed the deep fragility of the arts sector, leaving it largely dependent on precarious corporate and brand sponsorships, along with philanthropic generosity. But why has arts funding become so reliant on these sources, and could the arts sector find another way forward?

“There is money, it’s just so unevenly distributed”

Following Baillie Gifford’s funding withdrawal, book festivals and the British commentariat turned on the Fossil Free Books activists, devoting column inches to blaming them rather than dissecting the underlying crisis that leads to harmful funding sources. What could have been a pivotal moment for change was instead spun into a cautionary tale about disrupting the status quo.

“We were presented as a bunch of immature children running around, asking for the world to change overnight, when actually, [we were showing] real diligence,” says Vanessa Kisuule, a writer, performer and campaigner for Fossil Free Books. She points out how companies that claim divesting is impossible have made exceptions when it suited their interests, citing the swift action many took after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“What could have been a pivotal moment for change was instead spun into a cautionary tale about disrupting the status quo.”

Bloomsbury, one of the UK’s largest publishers, demonstrated that alternatives to Baillie Gifford’s sponsorship exist, stepping in with £100,000 in funding to help fill the void left by the company’s withdrawal. “Across all the festivals that Baillie Gifford funded, the total money was a million pounds. If you rattled your collection tin around the big five publishers, they can find that money,” Kisuule says.

The challenge from Fossil Free Books was bold but necessary. “Let’s be dynamic. Let’s be collaborative. Let’s actually think about the fact that there is money – it’s just so unevenly distributed,” Kisuule tells Skin Deep. “Yes, we’re in an economic downturn right now, but there are loads of companies who aren’t complicit in genocides and ecological collapse and who want to be involved in the arts and put the money towards good things.”

In recent decades, the state of public arts funding has been nothing short of abysmal. A recent report shows that while Germany, France and Finland each increased cultural spending by up to 70%, Britain cut its budget by 6%. “When Thatcher started privatising everything, culture and the arts followed that trend,” says Zarina Muhammad, one-half of The White Pube and co-author of Poor Artists. The art critic says that the neoliberal policies of the 1980s and 1990s began to redefine how the arts were funded, setting the stage for an increasing reliance on private sponsorship.

“When Thatcher started privatising everything, culture and the arts followed that trend”

1992 marked a significant milestone, Muhammad tells me. It was the year Tory MP Norman Lamont introduced the Private Finance Initiative (PFI), a model for public-private partnerships that was supposed to be mutually beneficial. “We know how it happened in hospitals, schools, rail, etc., but it leaked into the arts,” she explains. This shift, initially presented as a way to enhance funding, ushered in a model where private finance began filling the gaps left by dwindling public investment. The consequences of this approach would only become more pronounced in the following decades, leading to the funding landscape we’re seeing now.

The real blow came during the austerity years under David Cameron’s coalition government. “They just sliced away all the public funding with the argument about the deficit – they cut cultural funding to the very bone,” Muhammad says. Since 2017, funding from national arts bodies has declined by 16% in real terms across the UK, with England experiencing an 11% drop and Wales a staggering 30% reduction. The Tate serves as a prime example of this transformation. Muhammad explains how, during the Blair era in the late 1990s, 70% of Tate’s funding came from public money, with only 30% from private sources; “Fast-forward 20 years to the Conservatives,” she says, “and it flips the other way – 70% privately funded, 30% publicly funded. The deceleration of public funding is a hard gear shift. These cuts changed everything.”

Suffering artists

Top-down government decisions on public funding have not only affected the national landscape, they’ve also starved local councils, which were once also significant funding sources. These are now forced to reduce or even eliminate arts funding under mounting financial pressures. The ripple effects are not only destabilising institutions but also workers, who are facing increased precarity due to low wages, worsening working conditions and rising costs of living. In 2018, Arts Council England revealed that only 7% of visual artists earn more than £20,000 annually. In 2022, the median earnings for authors were shown to be just £7,000.

Naomi*, a 28-year-old illustrator with eight years of experience, shares her struggles: “Half of the publications I have worked for have shut down or simply don’t have the budget to pay illustrators anymore. I never imagined I’d be in this position at this point in my life, especially after my career got off to such a wonderful start.” While some corporate and brand work remains available, she explains that these opportunities are scarce, competitive and creatively limiting. “It usually means there’s less space for innovation or fun in the art you make,” she says, reflecting the growing trade-offs between making ends meet and artistic freedom.

“The response of many culture managers to what’s happening in Gaza and Lebanon has very often been to apply a rule of silence. Artists find this intolerable”

“The ongoing dismantling of social safety nets through austerity has continued to narrow who can afford to be an artist,” say organisers at Artists and Culture Workers LDN, a members’ organisation, for people who work and organise in the culture sector. “Cuts to arts education have had the same effect, reinforcing restrictions around who art and art-making are for. Public funding cuts also mean commissioning becomes increasingly risk-averse, with a focus on forms of visual art that are most commodifiable.”

Want to support more storytelling like this? Become a Skin Deep member.

As arts organisations turn to corporate sponsorship to fill these funding gaps, more often than not, they take on the agendas of their sponsors, willing to overlook greenwashing and human rights abuses. This financial reliance filters out critical or risky voices who might upset funders. “The response of many culture managers to what’s happening in Gaza and Lebanon has very often been to apply a rule of silence. Artists find this intolerable,” Farhana Sheikh, organiser for Artists for Palestine UK, tells Skin Deep.

Fixing the funding crisis

While increasing public funding seems to be one obvious solution to the current crisis, state funding doesn’t come without its own challenges – particularly when it comes to censorship on issues such as Palestinian solidarity. In January, Arts Council England updated its guidelines, warning that “overtly political or activist” statements could pose a “reputational risk” and jeopardise funding. Although this policy was revised in March, concerns lingered about its impact on artistic freedom. Meanwhile in Germany, where public funding for the arts is far more substantial than in the UK, artists have accused the government of suppressing pro-Palestinian speech.

If state funding through an arts body alone doesn’t fully address these issues, what other opportunities might exist to redefine the arts sector’s relationship with funding?

One approach is to look back at history, drawing lessons from the successes and failures of those who came before. For instance, the British community arts movement of the 1960s and 1970s sought to democratise art by empowering working-class communities to create work rooted in their own experiences and values. The project also sought to challenge elitism in arts institutions.

Another example is the Greater London Council (GLC), which – under Ken Livingstone’s leadership in the early 1980s – prioritised community arts as a central focus of its cultural policies by offering critical funding and support to grassroots artistic initiatives and pushing back against Thatcher’s undermining of the arts.

“Divestment within the arts isn’t just about rejecting unethical funding. It’s about reshaping the sector to align with the values it claims to represent”

“I do have a problem, though, with the idea that a national funding body has the power to say yes or no to an artist’s application to make something – that’s fundamentally always going to be structurally inequitable,” says Muhammad. She points to alternative models, like Ireland’s Basic Income for the Arts pilot, which provides artists with an unconditional weekly income to experiment and create without pressure for specific outcomes. While acknowledging its shortcomings, such as the risk of subsidising landlords without rent controls or enough social housing, she finds the model more promising than others. Muhammad also highlights Norway’s artist stipends, which subsidise creative practices over several years.

Divestment within the arts isn’t just about rejecting unethical funding. It’s about reshaping the sector to align with the values it claims to represent, and not forcing artists to choose between their values and their livelihoods. The Fossil Free Books campaign illustrates that the status quo – overreliance on private funding – is broken. While the scale of solving this challenge may seem overwhelming, collective action pushes the quest for alternative paths forward.

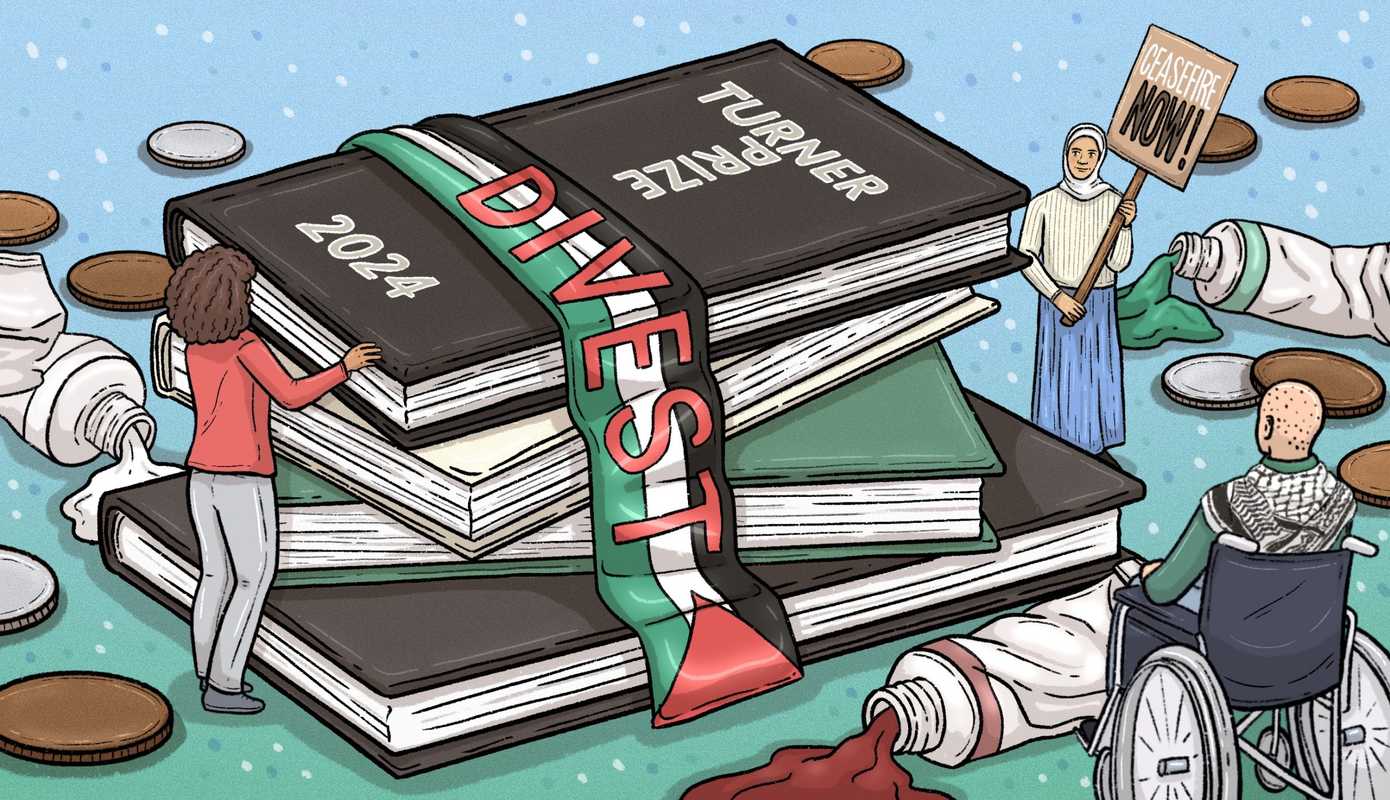

“Individual refusals feel like they mean very little, but that’s not the case when we collectivise our efforts,” Muhammad explains, referencing Jasleen Kaur’s Turner Prize acceptance speech, which added to the growing calls for divestment and solidarity with Palestine. Ethical sponsorships, crowdfunding, and cooperatives, combined with more robust and equitable state funding all present practical alternatives to reliance on harmful sources of income. We just need to explore them.

Stay in touch. Subscribe to Skin Deep’s monthly newsletter.