Our neighbourhoods are the centre of our universes and how they are perceived by us and others has tangible, life-changing consequences. Aicha el-Beloui is a Casablanca-based illustrator, graphic designer, and creative director who builds maps that put residents’ lived experiences at their heart. They confront toxic clouds of prejudice head-on, and play with a map’s innate abstraction through the use of the surreal. Ahead of the unveiling of her new work, MO(VE)MENTS, a map and travelling art installation that explores the multitude of stories behind the Moroccan presence in the UK, Skin Deep’s Courtney Yusuf caught up with Aicha to chat about the emotional power of our neighbourhoods, the political danger of phone addiction, and the enduring myth of Casablanca.

*

Courtney Yusuf: Have you always lived in Casablanca? Is there a particular part of the city that you feel connected to?

Aicha el-Beloui: Yes, I was born and raised here. Casablanca is a new city – the oldest part, the Medina, dates back to the late 18th century, but the modern city centre was built from the beginning of the 20th century. This section has an exceptional architectural heritage and a lot of styles – Modern, Art Deco… It’s hybrid. After the French colonisation, they decided that Casablanca would be the economic capital of Morocco. They needed to build the city and so invested a lot in it. It was a laboratory for architecture and urbanism. It’s really beautiful and before studying architecture and knowing its values, I knew it was something great – (laughs) I just didn’t know why!CY: You studied architecture in Rabat. Did you enjoy that experience?

AB: Not very much. I was disillusioned from very early on. I thought it would be about creativity, about a very romantic way of building a city, but it was nothing like that. You find that some schools might specialise in a technique or particular literature but frankly this was just about whatever that particular teacher liked. It was very different from one year to the next and it was a very childish and one-directional approach to teaching: from the teacher to the students. There was no exchange. This is not just specific to architecture and I think it has something to do with the school system in general here. I just wish we could have had more responsibility as students, opinions that we argue about, defend, and construct. Instead, it was just getting things from the teacher and trying to satisfy him in return. And that’s bull!

CY: Now that you have a deeper understanding of architecture, does it make you feel differently about Casablanca?

AB: It makes a big difference because I know a little bit about it from a governing point of view – the back office, the decision making. But what has made my understanding even richer is my experience as a citizen. I think our problem here is that the citizen doesn’t often see the city – we are not aware of our rights to it. In Casablanca, as in other – and I don’t like this word but ‘underdeveloped cities’ – our public spaces are just transition spaces. The most important thing is to keep oneself safe and so you are focused on going from point A to point B. That’s your mission. There’s no sense of ownership over the city. It belongs to the government, it belongs to the state, so I don’t care about it. When decisions are made to tear down a big part of the city or some very interesting buildings why does no-one care? The city is invisible.

I used to do guided walking tours in Casablanca with an organisation for twentieth century architectural heritage and people would tell me, ‘I’ve been passing by this building for forty years and I’ve never seen it before.’ This is very powerful – it tells us a lot about how we relate to our cities and how much we don’t know them. I don’t think it’s always been like this in Casablanca – it’s part of a political will. It suits people to have this chaos. You can play with it and nobody’s going to ask ‘hey, what are you doing with this neighbourhood?’ Or ‘what’s this decision you took?’

But it’s also the same in ‘developed’ cities. The city becomes invisible and taken for granted because you know that you are safe so you are always on your phone. It’s crazy!

CY: So you have an education in architecture but now you work in the visual arts – how did that happen?AB: Everything was triggered by the perception of Casablanca that I experienced when I was abroad. Whenever I said that I was from Casablanca people would say ‘Oh, that’s so romantic!’ There is nothing romantic! Every image that exists in the collective imagination about this city of six million people comes from the Michael Curtis movie that was not even shot here! We don’t exist anywhere except in a foreign fiction! I’m an illustrator now and I think that my job is to highlight this problem. With my maps, the starting point is always the collective imagination, the prejudgements of a place, or the lack of them. Take Marseille, for example, one of my latest projects. It started from the fact that every time I mentioned Marseille people were like ‘Why are you going there? It’s dangerous, it’s dirty and it’s full of Arabs! (laughs) Better stay home!’ There are so many judgements. When we hear about the northern neighbourhoods, we just imagine drugs and guns, a no go-zone. It’s a fantasy – a very bad image formed without even going there or knowing the people.

When I decide to work on a place I start doing research, which is an important level of mapping. I need to confirm my prejudgements or thoughts about a place in order to discover what’s really behind them. And lastly I collect stories from the people. That’s a very important part because they are the practitioners of an area. They are the ones who can tell the most about the current situation of the place. And then, of course, there are my own experiences of the place.

CY: How do you go about collecting the stories for your maps?

AB: It depends on the project but I usually just go to the place and meet the people. I prefer doing it in a spontaneous way. When I returned to Marseille, I went through the [official] structures and organisations, and I had a hard time reaching people because their reaction was ‘OK, someone who wants to use us again’. So I went to these areas and sat in the squares, where the mums and children are, and I just approached them with the Moroccan language. I was like ‘Hey, I’m here without my mum for three weeks. Would you mind talking to me?’ (laughs) And it worked!

We often don’t realise that it can be a very sensitive topic. People never talk or are given the chance to talk about their environment – it can be a very big wound, one that is ever-present in their lives. In Marseilles when I started talking to people, explaining in a clear way what I wanted to do and asking questions like ‘what does the area represent for you,’ and ‘what’s your relationship to the city centre,’ and ‘what’s your relationship like to where you originally came from?’ people opened up really quickly. Many started crying.

CY: Why do you think it’s such an emotive subject for people to talk about?

AB: When a place is full of negative judgements and there are people living there, they have to endure those judgments and no one hears their voices. You are giving them a way to be visible and to say ‘Hey, this is my view of the place that I live in every day. It’s me living here, not you.’

CY: What was the end product of your work in Marseille?

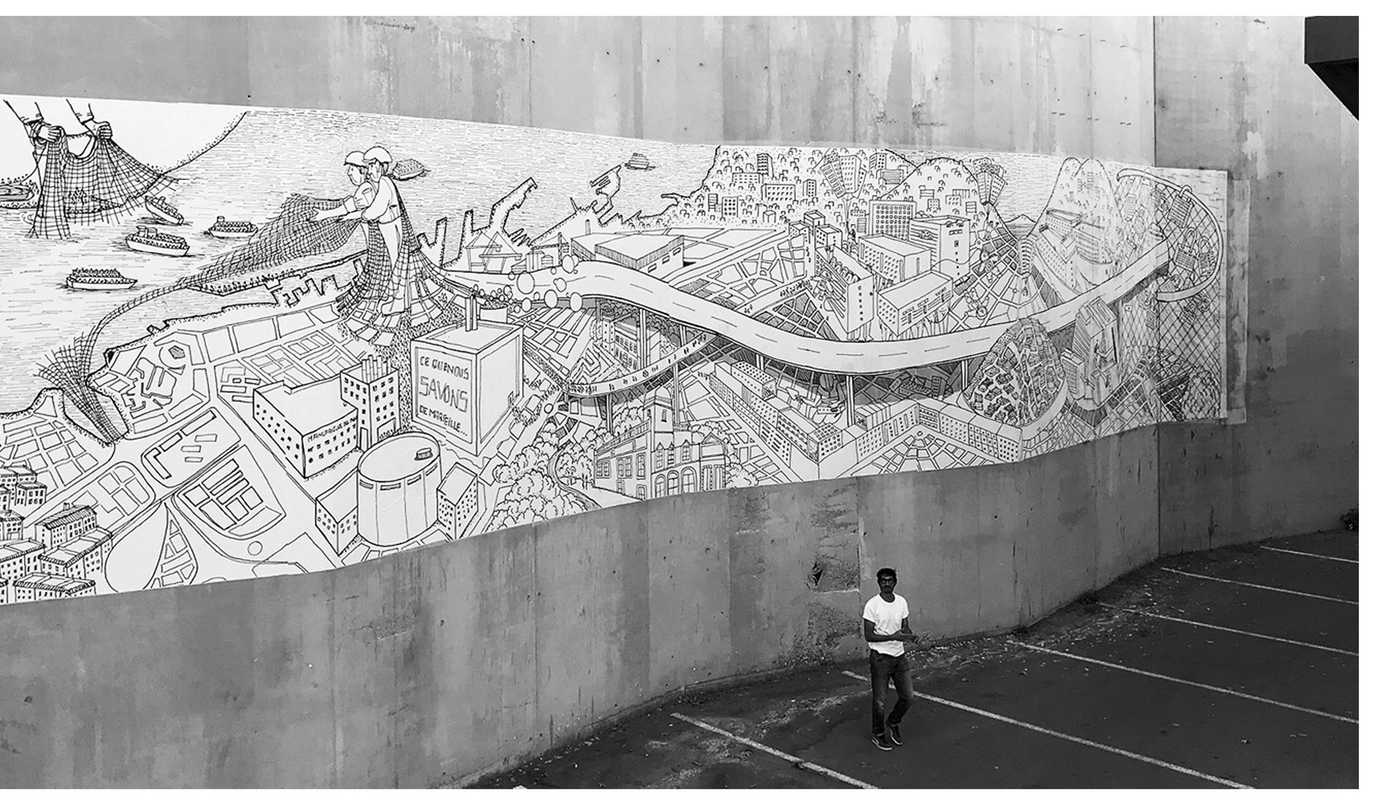

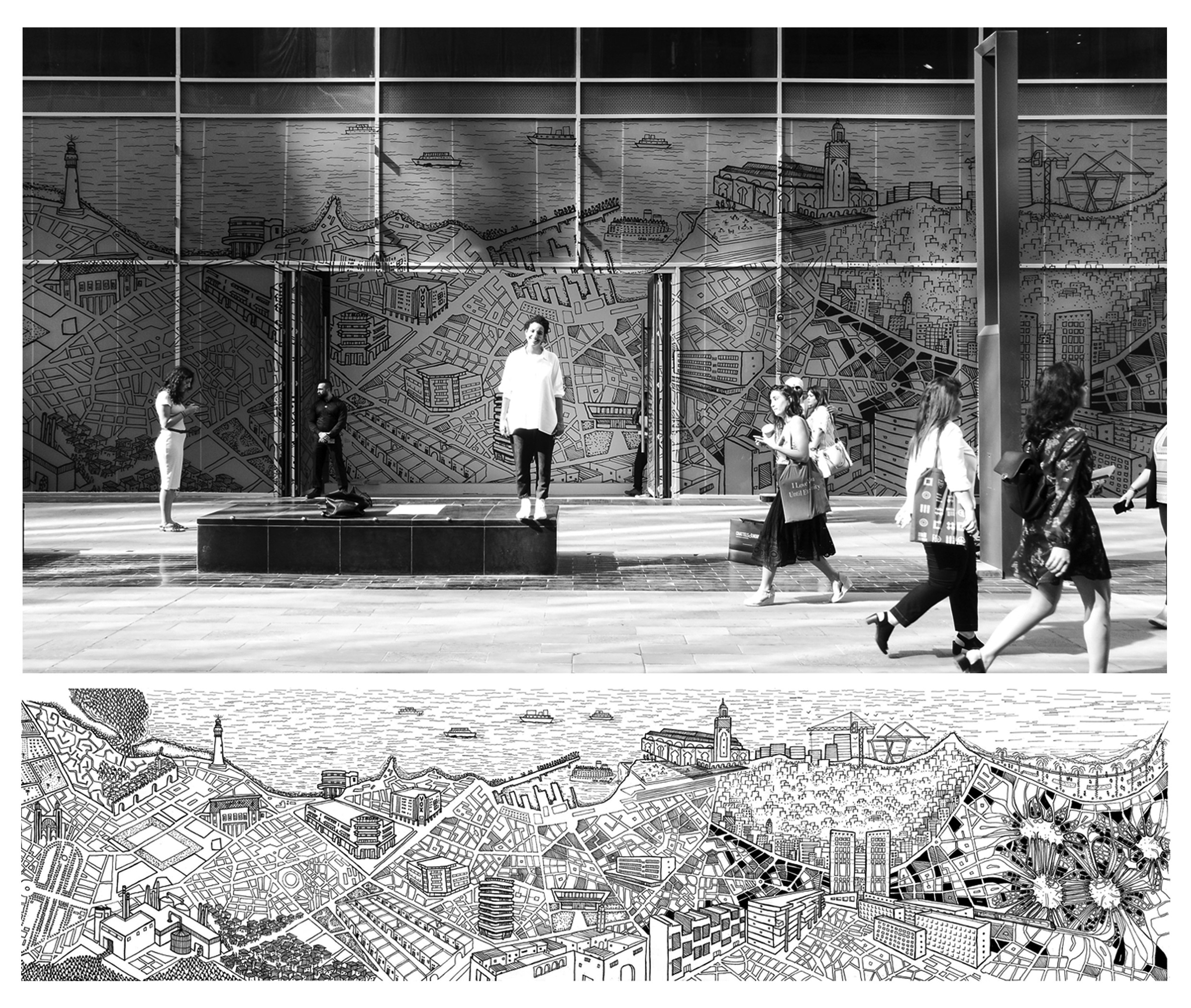

AB: It was a big map, four metres in height and 20 metres long, that represented the story of what I understood to be the effect and consequences of urbanism and architecture on three generations. I use collage and insist on a particular process of drawing on a small scale and then scaling up. It gives a feeling of being part of the drawing and scaling up is the same process used when a city is designed and actually built. Everything starts from paper, right? I also use small people on the maps because I really want the public to feel that they are part of them. That’s very important to me because I’m telling the story of a place through its people.

I find there is a lot of freedom in illustration, you can play with scale, you can play with elements, you can do whatever you want and express very strong ideas. I can’t talk or write very well about stuff so for me, drawing them is a great way to express reality in a very surrealist way.

Aicha’s latest work, MO(VE)MENTS, illustrates the multitude of stories behind the Moroccan presence in the UK. Built through speaking to people and community groups, researching the sound archives of the British Library and visiting many locations, MO(VE)MENTS exists as both one of Aicha’s distinctive maps and as a travelling art installation. The work, which will be unveiled on Saturday 29th June, was commissioned as part of London’s 2019 Shubbak festival -the city’s largest biennial festival of contemporary Arab culture – that starts today (June 28th) and runs until July 14th. Go check it out!

%20Joshua%20Virasami.jpg)