In London, I have gotten used to seeing straight theatre. Theatre that, either in structure or content, adheres to conscious markers of narrative and placates what feels to be the natural logic of the mind. Even when this theatre is explosive, when it has the kind of jagged edges that root you so immovably in the present, straight theatre is… clean. It mimics the tying of a knot. Its threads may frey open, but they will always, often neatly, come together again.

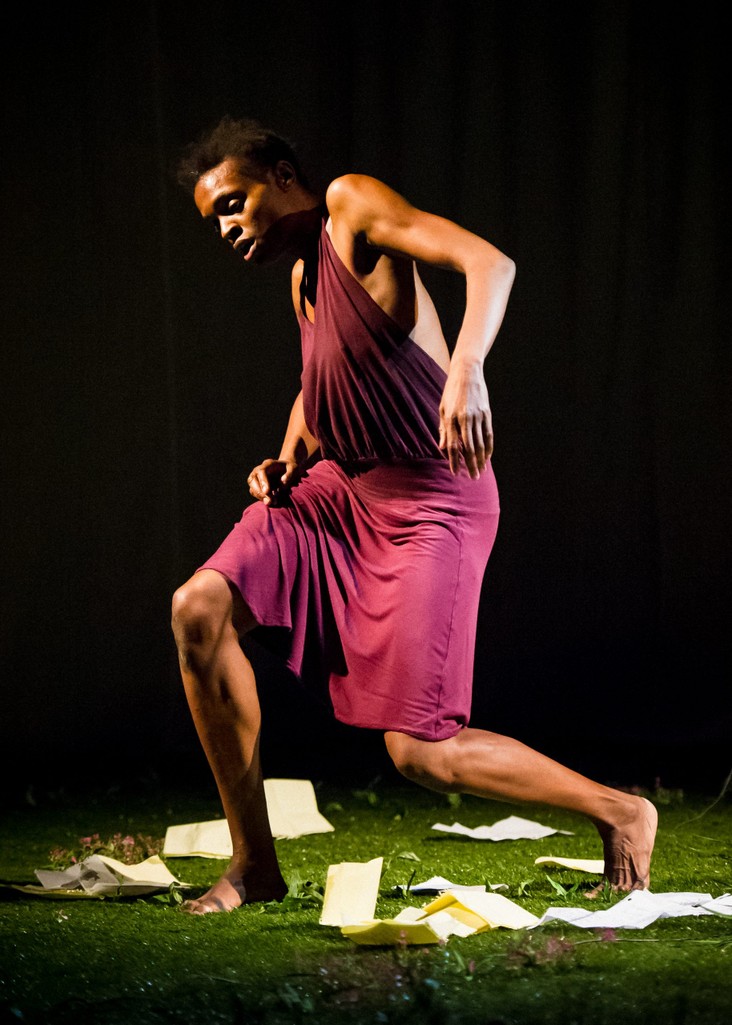

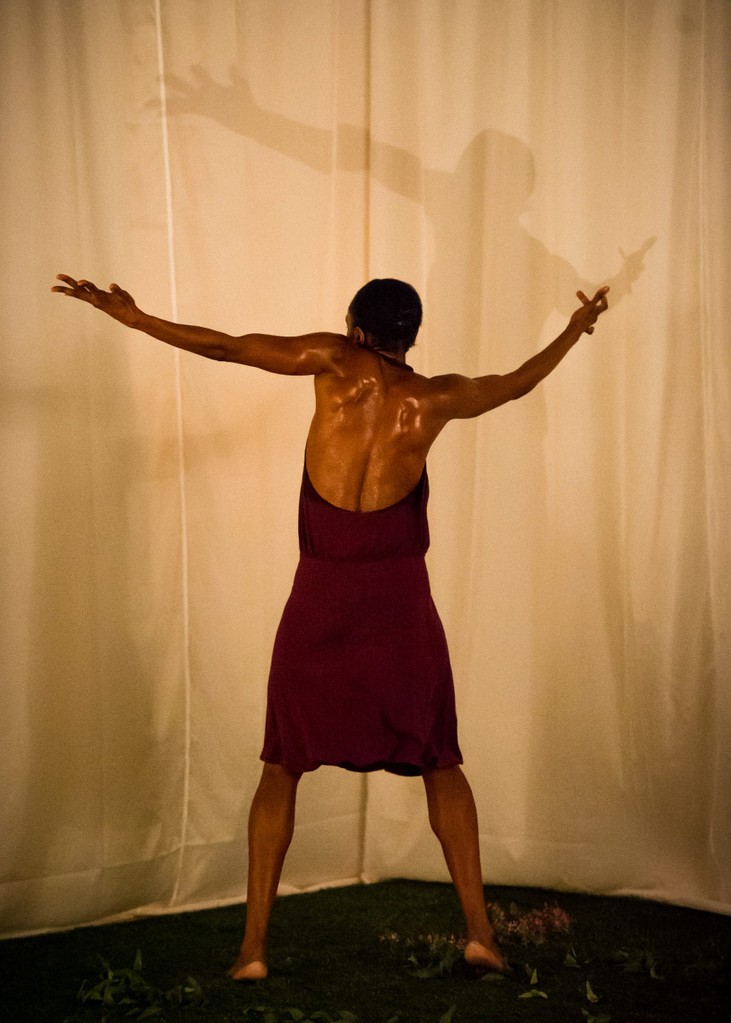

I love straight theatre but I also crave work that will shake my formal expectations, theatre that forces me to look beyond and between the words to find its own language. In that language, in the shadows and quaking, is the creeping weight of dramatised experience, and in the case of Bronx Gothic, the trauma, confusion, and the process of dissociation from it. Bronx Gothic, conceived and performed by Okwui Okpokwasili, is about a young girl who is sexually abused by her stepfather. It doesn’t just give you that though, instead it carries you along in movement, wonder and discomfort, holding your attention close until you finally realise what it is you are feeling, what it is Okpokwasili’s language conjures for you.

Bronx Gothic is turbulent, vulnerable, and its structural lines do not slot tidily in the mental spaces we are used to making as audience members. It is not a show that can easily be capped in a short review. I spoke to Okpokwasili about how she developed this work, the intentions she set for the piece and herself, and why she chose to explore this subject matter in this way.

Nkenna Akunna: How was Bronx Gothic conceived?

Okwui Okpokwasili: I started making it in 2012 and I didn’t yet have the commission so I didn’t have anyone supporting it. But people would ask me if I was working on anything and I would go and read pieces of it. I read a piece at La MaMa (NYC) once. I would also perform some of it at movement festivals. I pretty much stayed in dancer performance spaces when developing it. I think there’s a kind of fluidity there, a space for hybridity, and a welcoming of pieces that might challenge form and expectations of what we think we should be seeing. I was making it piecemeal, and I then got a commission with Dance Space Project in New York, and basically built this piece through that.

NA: The show opens before it opens, and by that I mean that as the audience walk into the theatre, we see a stage dotted with angular lights, plants and flowering cans, and you in the corner with your back to us, jittering and shaking.

OO: Yes, when people are coming into the theatre there is half an hour of movement. I consider that movement a prologue. It maps out where the character is going to go in the piece, and so in the spirit of a kind of prepubescent, it’s this idea of coming into a new body. Whatever anxiety I am feeling in that moment, it starts to go away and I feel like I am this other.

NA: How did you conceive of that particular movement? That quaking?

OO: It started with me thinking about what would happen if you tried to twerk for way too long. Like, what happens if the twerk goes terribly wrong? I thought about certain popular forms of movement, specifically movement that has very obvious sexual connotations but at the same time is also about a certain kind of joy. I grew up with people dancing like that in my Nigerian home and at Nigerian weddings and parties, and also growing up in the Bronx, that’s what you did at a party, people danced from the hip. I’ve seen children do it. But still, we project its meaning and we project on children, [we question] whether they can be children when we see them doing certain things. So I thought: what if I took this particular vocabulary that creates a sexualized idea of who is doing it, but is also about freedom? I felt that it was a powerful movement to try to do to failure. You’re watching me do this and you’re not sure what it is anymore, so you don’t know how to determine [what you’re seeing].

NA: It felt like multiple bodies coming in and out.

OO: The piece is trying to make you feel uncertain. It’s about how you should position yourself in relationship to what you’re seeing. Often a lot of us, when we go to see a play we say, I am this person, and this is who I’m rooting for, and I believe this, and I definitely agree with this or that, and I also feel like whoever is on stage totally knows what they are doing and they’re stuck in this piece.’ I’m really trying to upset those expectations. Maybe there are moments you are watching and you’re like, ‘wait what?’ And I’m like, ‘no, you what!’ I’m hoping that these expectations, about what the relationship is, can shift somehow. It’s changing in the moment and I want to be alive to what is happening in the moment.

NA: When I think of how I would try to describe the movement in the piece in general, the word rupture comes to mind. You are presenting yourself as two different voices, two different people, and then there comes a distressing point where I started to think, ‘this may be one person.’ It was the first time you did that sequence with a plank position, and then you repeated it, and repeated it…

OO: Yeah, I always call it broken body.

NA: It’s difficult to watch because it feels like the act of what was happening to this young girl, and her body not being her own in that moment. It felt like a body being moved into space without consent. And so that alongside the quaking, at the beginning and throughout, it made me think of the separation of the body and the mind through dissociation. And all of that is contained in that movement. It is like it’s own language.

OO: It’s true, this is another kind of speech.

NA: And it is a speech that works with the spoken language that you build around it. Can you talk about the choice to have a lot of the narrative in this piece happen through written notes and letters?

OO: I thought to myself: can I do an epistolary narrative? It’s not just Jane Eyre! When I was younger I would read those novels, and as I got older I would think about how we passed notes to each other and how through that, another world happening. I wanted to see how far that could go. I think the piece does continue to try to create a dynamic relationship between the movement of the body and the text. How do these two things charge each other, how do they contradict each other? How do they co-exist? Exactly when there is no more speaking to be done, the body just… erupts.

NA: I just want to summarise my understanding of this piece. This work is about a young black girl dissociating from her body as a result of sexual trauma. She is presented as multiple minds, in letters between two young girls. This is a girl with many voices in her head, and so this is a show about mental health. I think about her dissociation not only as a method for coping with trauma, but also a separation from her childhood. This is a girl being forced into an adult much earlier than she should be. This idea, this sense of a shortened childhood, is a reality for many young, black girls.

OO: Yes. There are so many of us who were not told [about our bodies], we were not supposed to talk about it. And yet when I was growing up, there were nine year olds having their periods, breasts developed, walking to school by themselves, walking to school with friends and always being addressed or accosted by random men or older boys. So it did feel like this innocence was cut off. It is so easy to be like ‘well, she’s wearing short shorts, and the way she walks is…’ but where is the space for girls to be in touch with their own sexuality? To explore, to experiment, to come into themselves? That discovery is a part of innocence. And so, this piece is thinking about how to contend with a kind of knowledge and awareness that I think is good, alongside the violence that might have created that awareness. Navigating this question, this in-between space…

NA: And the reality of black women’s and girls’ bodies as the site of others’ experimentation…

OO: Hortense Spillers talks about this particular space that black women occupy: through the black woman, you could move from humanity to animal, because at least in the United States, any issue from the black woman after the institution of slavery was a slave, no longer a human, no longer entitled to the protections or imbued with the rights that were supposed to be inherent to being human. We have occupied that space and in some ways I think we still occupy that space. We’re not woman, we’re not human, but we create this excess capital that is used and abused and discarded anyhow. [With that space in mind,] how do we see ourselves in our own bodies? Clearly this is a character who is in that question. And she is fragmented. The piece is a quest to make some kind of cohesive self, but it will ultimately fail because of the trauma. Maybe because we have to figure out how not to cohere in the ways that we are supposed to? I don’t know. So, the piece also ends with a question: what now? Now that I have discovered certain things… how does it all come together?

Bronx Gothic is on at the Young Vic until 29th June 2019. You can get your tickets here.