Changing Face is an international drama and documentary theatre company. Their work is informed by international stories and experiences – from Romania to Rwanda, Kosovo to Kurdistan, Bangladesh to Britain. Ahead of their series of new plays, we chatted with their co-director Lucy Curtis about creating political theatre about gentrification, police brutality, and daring to dream.

Skin Deep: Where does the name ‘Changing Face’ come from?

Lucy Curtis: We’re interested in making work informed by and responding to our experiences of living in communities around the world that are in a constant state of change. Our first production, Where Will We Live? – a verbatim play revealing the human face behind Brixton’s hyper-regeneration – was an urgent interrogation into the way Brixton, our community, was changing. It became a dialogue for participation, for residents, developers and politicians alike to speak openly about the future of Brixton, which really wasn’t happening at the time.

We also work with artists who are challenged and encouraged to take on projects that are perhaps completely removed from their own experiences; we try to work with the same artists over a period of time, so it’s symbolic to their craft and to the ever-evolving and changing genres we work with.

SD: How would you describe the type of productions that you produce and platform?

LC: Urgent, dynamic, rough. Our work is about understanding and being understood, stories full of messy, honest human behaviour. We don’t limit ourselves to just one style; we work with a multiplicity of stories and artists making sure that no voice, no matter how small, how poor, how outcast, is lost. We work with photographers, illustrators, film-makers on text-based pieces, installation, documentary and movement.

A lot of us were brought up in cultures completely disconnected to the ones our parents grew up in, so cross-cultural storytelling is always at the heart of what we do, connecting people to a world of stories, old and new. We’re currently building relationships with international artists and starting to tour work outside of London, which is important to us.

SD: Your productions have been called “Intensely political, and carved from the living streets that surround [the stories].” Do you think your work is political because it explicitly seeks to cover political issues, or rather that it is politicized because the communities that your productions engage are often viewed as ‘battlegrounds’, whether that be in terms of real life conflict (Kosovo) or ideological struggles to define these spaces (Brixton)?

LC: Whether or not a piece of theatre is explicitly so, for me it is always political. When you’re dealing in emotions, society and people, it has to be. I’m interested in how theatre can be used to engage a wider audience from a far more diverse background than currently witnessed; bringing communities together and re-empowering the theatre with its most important asset: the human.

Our work is born out of a need for theatre to address issues that should not be ignored. For instance, we’re currently developing an Irish play with a Northern Irish writer who grew up in the height of the Easter Rising as a Protestant and who was nearly blown up by a Provisional IRA bomb. 2016 was the centenary of the Easter Rising and there was hardly any theatre that responded to this, in London at least, so we found a playwright who we knew could work with us on delivering something that challenged this. The tone of inter-community conflict in Northern Ireland which the play deals with is getting louder in Britain following Brexit, so a play that was written at a time of great darkness has something to say as the shadows begin to lengthen once again.

Our Brixton project was born out of sheer urgency to create some sort of participation within a community that was given absolutely no participation at all by local politicians. The piece sought to challenge and uncover the ideological struggles, sure, but it was more about the human stories that underpinned the movement, and that happened to address the deep social divides that were neglected in Brixton. We worked to expose these as we interviewed our participants, but we also wanted to celebrate the people that made Brixton the community it was pre-2016.

SD: Being based in Brixton, how has gentrification in the area affected your work in documenting the lives of the community? Has there been a change in the way the community engages with theatre and the arts?

LC: I think Brixton has always engaged with performance, it’s built itself on it. You walk down Brixton High Street and you’ll see performers of all different ages: street preachers, drummers, start up bands. It’s the birthplace of Bowie, Max Wall and Linton Kwesi Johnson. More artists live in Brixton than anywhere else in Lambeth. There’s not been a theatre in Brixton for a long, long time, so the theatre really has become the streets. It’ll be interesting to see, when Ovalhouse move to the area next year, how a four-walled building will change the dynamic and who they’ll be able to engage. Obviously Brixton’s demographic has changed and theatre is still pretty inaccessible as an art-form once you box it inside a building, so time will tell whether a theatre in Brixton will fuel connection or house prices.

The experience we had on Where Will We Live? was special because everyone we met on that journey has now moved out of the area, and it was at a time where Brixton was on the brink of changing forever. That change has happened now and we’re the poorer for it – creatively, culturally, socially. At first, I felt so flat after the evictions that I didn’t know whether I still wanted to live in Brixton. It’s hard now to document the lives of the community because much of it has been replaced by faded businesses like Costa and burger joints. We have continued to collaborate with Brixton-based non-profit organisations: in our next play, we will be working with ‘The Advocacy Academy,’ a social justice fellowship for young people who want to make a difference in their communities, offering free workshops in making theatre to do so.

SD: One of the really exciting initiatives you just produced was a project called Dare to Dream, which emphasised plays that dealt with “borders, barriers and boundaries; what it means to overcome these and to delve into a world of second chances, courage and wonder”. It’s incredibly timely for you to be putting this out right now, but what’s especially poignant is the way you’ve phrased it; you wonderfully position immigrants as active agents who, unlike so many of us, continue to dream of something better or a place that is not yet here. That’s quite powerful. Could you speak a little bit about the thinking and inspiration behind this project and why you think this notion of ‘daring to dream’ is particularly relevant to immigrants.

LC: I guess it came out of the need to find some hope and bringing people together to do so. I found it quite wonderful reading so many submissions of scripts about people’s dreams and how they interpreted the brief, which was purposefully left open. It’s terrifying to dare to dream, especially when those dreams are so hard to fulfil. It removes us from what we know, who we are and how we define ourselves. It makes us test and challenge. Where we lack identity, we are seen as aliens, others, strangers. I think that’s particularly relevant to ‘immigrant’ – that word encapsulates the ‘other’, the ‘between’.

SD: Finally, of all the plays you’ve put on, which one was your favourite? And what can we expect to see from you in the next couple of months?

LC: All of our plays have been so challenging, perhaps because each has been so much bigger than us. I’ve learned a lot from each process and each one has been drastically different. I’ve really loved working on It Is So Ordered by Conor Carroll – our upcoming play which premieres at the Pleasance Islington from April 5th-16th – because it’s been such a journey. It started as a 20-minute piece that won a place in the McConnell New Writing Fund, and it’s gone on to receive development and support from the Old Vic Lab and Park Theatre. I’ve enjoyed working dramaturgically with a writer, watching the piece evolve, and for possibly the first time, working on a play that I can’t draw too many parallels with. It’s a play about the wrongful and racially-motivated imprisonments of Black Americans during the 60s and 70s in Harlem, New York City. It couldn’t be more different to my own life. So it’s going to be a challenge, but I totally trust the creative team to pull it off.

Changing Face are also producing a UK Premiere with the Arcola Theatre and York Theatre Royal, The Pulverised, written by Romanian playwright Alexandra Badea and directed by Romanian director Andy Sava. It’s about the future of work, told by four people from four corners of the world, who all work under one multinational corporation. It is a play about overcoming barriers and striving for connection and intimacy, constantly trying to keep up with the rat-race of production line. It’s on at the Arcola Theatre from 2nd-27th May and will head to York Theatre Royal from the 31 May – 10 June. Come on down.

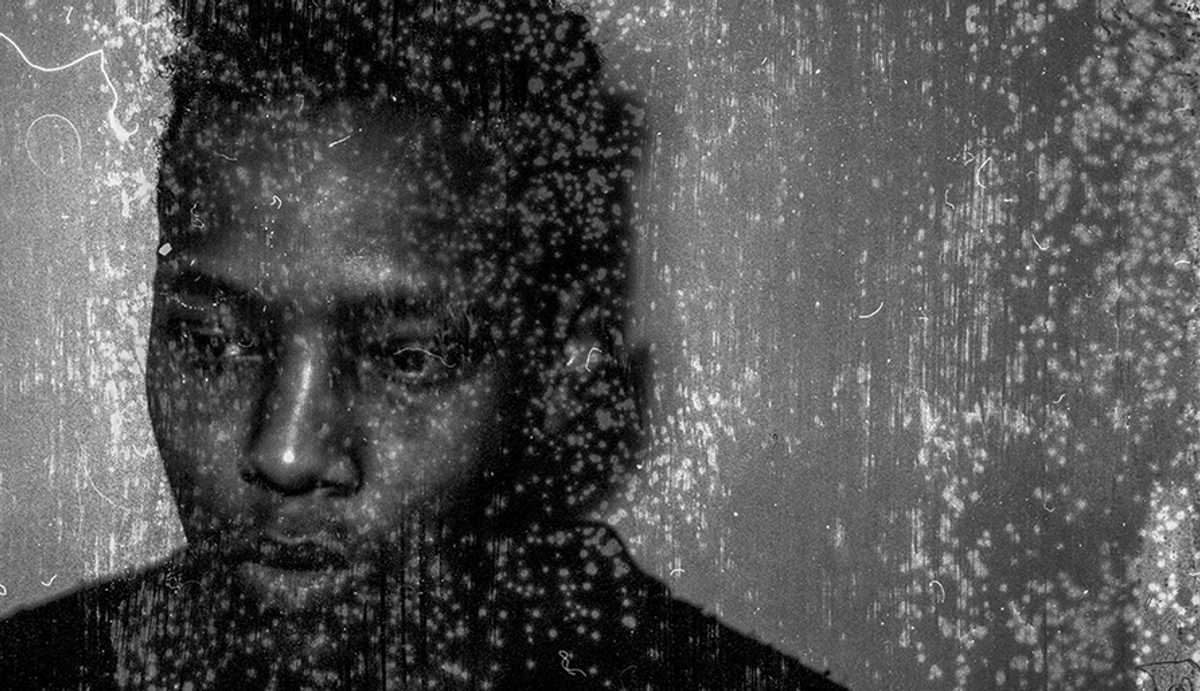

Skin Deep meets Changing Face

We chatted with director Lucy Curtis about creating political theatre, gentrification and daring to dream in the wake of Brexit and Trump