“North west 10 we are stepping, because we here and we just can’t leff it/

North west 10 we a’ make a move, because we have not a ting we go’ prove”

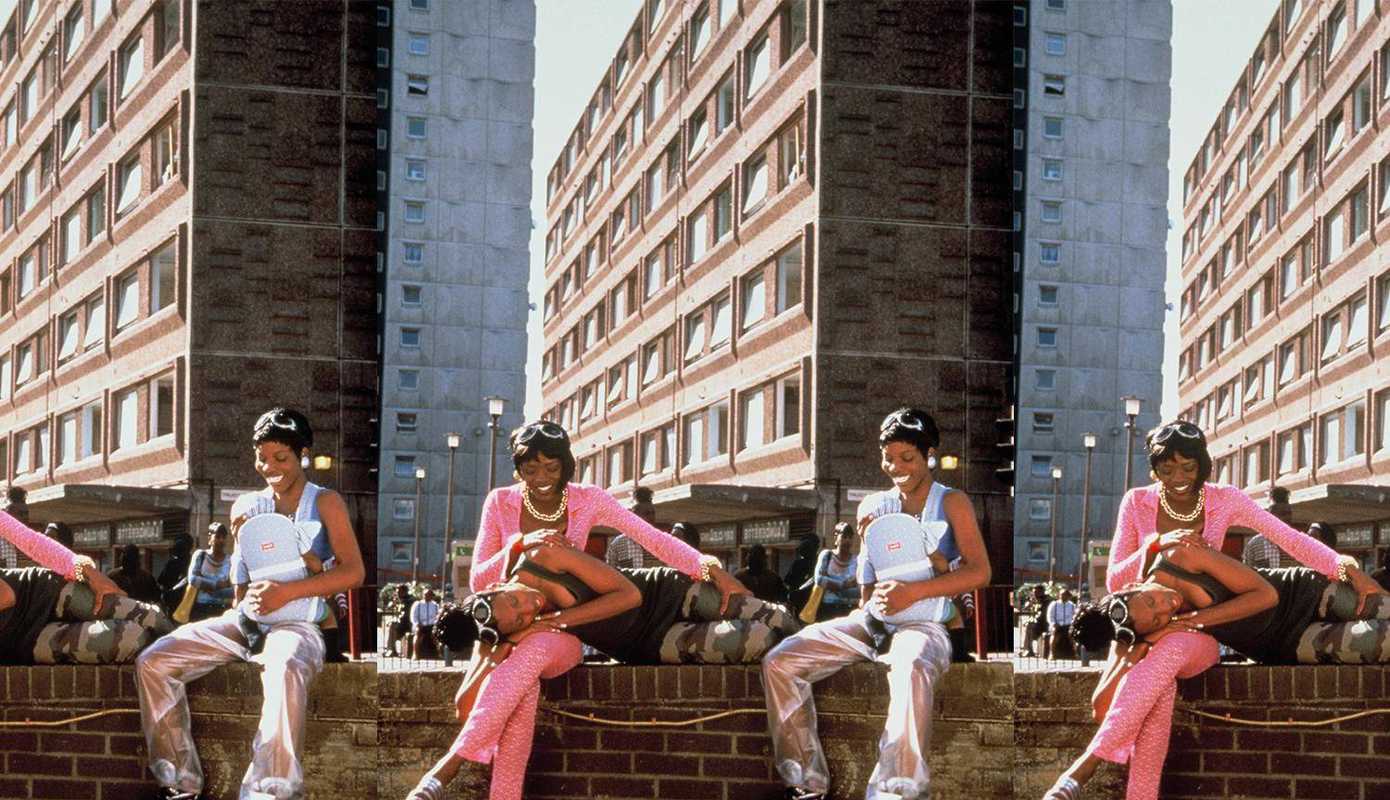

It’s 1998 in Harlesden, north-west London, and a crowd is gathering around the red clock tower on the highstreet. A bouncing ragga beat is playing and Anita (Anjela Lauren Smith) and her best friends are singing, dancing, and laughing together. Their twisting and winding is almost as head-turning as their neon outfits, and as their children dance with them the crowd cheers on. This is Babymother, one of the British Film Institute’s ‘Top 10 great Black British films’, and its bombastic opening scene sets the story of a woman chasing her dancehall dream as she raises two children in the UK’s ‘reggae heartland’.

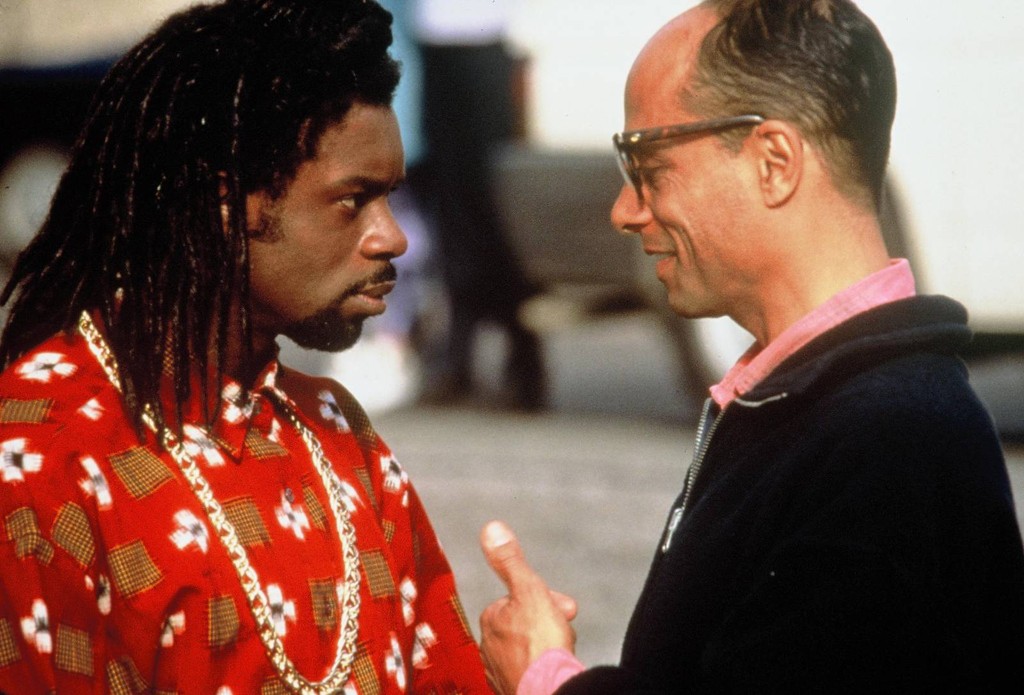

When I meet Julian Henriques and Parminder Vir, the film’s director and producer respectively, it is another sunny day in Harlesden. The clock tower is now blue, the road around it pedestrianized, but the streets are as busy as ever. In respective du-rag and zebra stripes, the husband and wife team are taking me on a tour. Today Julian is a professor at south London’s Goldsmith’s University, specializing in street technologies and cultures (particularly reggae sound systems) as joint-head of the Media, Communications, and Cultural Studies department. Long inspired by the intersection of music and film, particularly that of his Jamaican roots, by the time Babymother’s production started in the mid-1990s, Julian had already directed his short dance film Exit No Exit in 1987 – “It’s basically an Orpheus Myth on the Northern Line” – and We the Raggamuffin in 1992 – a short drama following a reggae singer evading two hit-men through Peckham. After this, Julian tells me, it was time to make a feature: “If you want to make a film about a culture, you have to go where it’s happening, where the sounds are being made. And at that point, Harlesden was the home of reggae music”.

The 1960s and 70s had seen iconic reggae record labels like Trojan and Jet Star burst out of this corner of the capital, alongside dozens of record shops and pirate radio stations catering to the Jamaican and Caribbean communities that had made Harlesden their home. Residents included artists like Dennis Brown, Jimmy Cliff, Janet Kay, General Levy, and even Bob Marley was living in neighbouring Neasden.

“And it wasn’t just music and record shops here, you know,” adds Parminder as we wind our way past the midday shoppers. “There were a lot of Caribbean takeaways, and shops that reflected what young Black people were wearing in those days. Harlesden was and is incredibly alive”.

Want to support more storytelling like this? Become a Skin Deep member.

Today Parminder works with entrepreneurs and microfinance in Nigeria, but her career in the arts kicked off in the wake of the 1981 Brixton uprising. “Just like after Black Lives Matter, institutions realised then how disconnected they were from communities”. Of Punjabi heritage, in 1984 she was appointed head of the race unit within the Greater London Council’s arts department. There she supported projects like ‘Third World Cinema’ film festival and creatives like Isaac Julian and Yvonne Brewster, before producing documentaries for the BBC and Channel 4. By the time Babymother was conceived, Parminder and Julian had been married for a decade and were living in nearby Kensal Rise as what were then called ‘Buppies’; ‘young, urban, black professionals’.

We stop at one of two remaining record shops on the street – now a small corridor only big enough for CDs. Still, as we poke our heads in, the sun on our backs and roots reggae in our ears, the record shop remains a portal. As Babymother jumps between a now lost musical world of record shops, recording studios, and nightclubs, the soundtrack doesn’t just frame the film, it drives it – with the characters performing the songs in what is in effect a ‘reggae musical’. Carroll Thompson, a singer once dubbed the ‘Queen of Lovers Rock’, was the film’s musical director. “Carroll had great musical knowledge”, explains Julian. “It was all about going to musicians we liked and getting them to write lyrics that could tell the story”. This meant working in Jamaica with reggae legends like Beres Hammond to create a smooth Lovers’ Rock melody for Anita’s babyfather, or with local musicians like Superflex for the proudly territorial ‘North-West 10’ ragga track that opens the film.

Creating larger-than-life musical sequences helped to convey a dancehall’s intensity. “I used to go with Julian to the dancehalls as part of our research – tiny basement rooms with all the bodies, the smoke, the colour, the loud music!” Parminder recalls. “The experience is an experience”, jokes Julian. Through using saturated colours and wide Super 35mm film, Babymother’s bombastic aesthetic also attempted to reflect the sparkling vision of how the Harlesden reggae scene saw itself, even if the true experience was not as glamorous: “We moved right away from a nitty gritty documentary style because I wanted to show respect to the scene and represent it with the production values that, if you like, it had in its imagination but perhaps did not always achieve in its reality. The film was a way of putting it out as its best self”.

Next we stop and smell the green banana and breadfruit outside a sprawling grocers. There’s a scene filmed here where a flippant Anita begs her tired mother to look after her kids while she goes out, for what seems like the millionth time. As the film progresses and we learn more about their relationship, we begin to understand how a distant approach to parenting can often repeat itself. It was these more intimate, familial dynamics, particularly those between women, that the pair believed were missing from the media landscape. “The woman’s side of this world, and the role women play in Caribbean culture – we wanted to give recognition and glory to those stories” explains Julian. “So many films like this are all about the exterior, what’s out on the streets. We wanted to tell an ‘inside story’ – what happens inside the home”, adds Parminder.

Next up is a church hall, now used as a vaccination centre with the freshly jabbed sitting outside. Following flyer runs and shout-outs on local pirate radio stations, anyone from the community could audition here for parts in the film. For Julian, using non-professional actors tapped into the creative talent of the local music scene – “as musicians, they have their own stage presence in performance and the whole casting process was trying to tap into that.” It ultimately paid respect to the community at the film’s heart: “I wanted to get it right as a principle of filmmaking. That’s what it’s all about, you know, building capacities and confidence, recognising and giving respect to the talent and creativity that is there. So there was never a question of doing it any other way. It had to come from the root to be true to the root”.

Eventually the bustle thins and the shops become houses. Parminder points to a small community centre where they did the first full script reading: “Do you know how hard it was to get executives, white executives, to come here?” It’s been clear throughout our walk that Babymother was not an easy film to get off the ground. “It was a massive hustle. You were constantly selling and pitching to white middle class commissioning editors who lived in a world fundamentally different to the realities of where we were pitching our stories from”. “So the challenge as a filmmaker”, Julian adds, “is finding ways to make sure that the production process doesn’t destroy what it is you were initially going after. But we now recognise just how difficult we had made it for ourselves, just by the nature of the product. You know, a reggae musical with a local cast and a first time director and producer. We had really stacked it up!”

The final stop on the tour is the Stonebridge Estate – it’s where Anita and her children live and where she looks out at the city to contemplate her path. Back then the high-rise complex was notorious for violent gun crime. “I remember being on a night shoot here” recounts Parminder, “It was three o’clock in the morning and flippin’ freezing. I was standing there when this young man came over and said ‘We have a lot of shooting here, you know’. And I said ‘Oh, what was the last film shot here?’ and he said ‘No – I mean gun shooting. You see those two bins, that was only a few days ago’. I was like ‘Oh my God!’ But with the local dons as our security, we could be there on the most notorious estate at three in the morning and feel absolutely safe.”

Nowadays, Stonebridge is unrecognisable. The majority social housing blocks are now low and interspersed with green spaces and a healthy-looking River Brent. For Parminder, despite all the challenges of the past, the film and television industry is also looking better: “Today both Netflix’s Vice President for the UK and the head of UK features are black women. That was unheard of at that time”. Julian agrees, “There are more opportunities and in terms of getting films recognised, they know how to market things now”. So much so that a new generation is watching Babymother today. Bukky Bakray, recipient of BAFTA’s ‘Rising Star’ award for her role in 2019’s award-winning Rocks, recently got in touch to say what watching the film had meant to her. “It is just so magical’, Parminder says with a cheer. “The spirit of collectivity and solidarity amongst creatives is much greater now”.

And if Julian learned one thing from Babymother? “Basically, don’t second guess anybody. If something is worth doing, it’s worth doing because you feel it and know it. Don’t try to find something that you think is going to appeal. Because if it isn’t appealing in your heart and in your soul, you’re not going to have the strength to see it through the journey”.

And with that, as I part with a wave and a smile, Julian and Parminder duck into a Trinidadian takeaway and our scene draws to a close.

Babymother is being screened at Peckhamplex on the 23rd October as part of ‘South by South’ curated by Tega Okiti. You can find tickets here. Our co-director and associate director of Rocks Anu Henriques will be hosting a workshop on the same day, preceding the screening, on ‘storytelling from the centre,’ alongside Freedom & Balance Headmaster Andre Anderson. You can sign up to the free workshop here.

Stay in touch. Subscribe to Skin Deep’s monthly newsletter.