Originally published in 2018, this archive piece is featured in Anthology – a collection of old and new stories that marks ten years of Skin Deep’s work in culture and racial justice. Order your copy now.

MAY THE DEAD CLOSE THEIR EYES, AND THE LIVING JOIN HANDS

– Memorial stone in Hagwi-ri, Jeju

Between 1947 and 1954, the rocky volcanic island of Jeju, lying off the south coast of Korea, witnessed a civilian massacre so large that it was topped only by the casualties of the Korean War of 1950–53. The killers were soldiers of the South Korean and United States Armed Forces. Over a seven-year period they murdered an estimated 30,000 people, or 10% of the island’s population.

It began with a child. On March 1st 1947, citizens of Jeju gathered for Independence Movement Day celebrations. Jeju was reeling from crippling unemployment, bad harvests (made worse by grain requisitioning by US forces), and the shock of having the country split in two and placed under the “trusteeship” (read: occupation) of the US and USSR, scarcely moments after independence from Japanese colonial rule. The official celebrations were brief, but the crowds did not disperse, spilling out onto the streets in a spontaneous protest. In the chaos, a small boy was trampled by a policeman’s horse. When the angry crowd closed in, police opened fire, killing six civilians including a school child and a breastfeeding mother.

Instead of an apology, the police issued a curfew, and after a general strike organised by the Jeju branch of the South Korean Labour Party (in which 95% of the island’s working population participated), they imprisoned 2,500 people. Clashes intensified over the following year, and on April 3 1948, a 300-strong group organised an armed uprising, protesting the US occupation of South Korea and its sponsoring of a South Korea-only election, which would effectively legitimise the division of north and south by creating separate governments. The uprising was short-lived, but the resistance of Jeju’s citizens was not. When the south-only election went ahead on May 10th, islanders boycotted the election, becoming the only region in the whole country to have their results declared void.

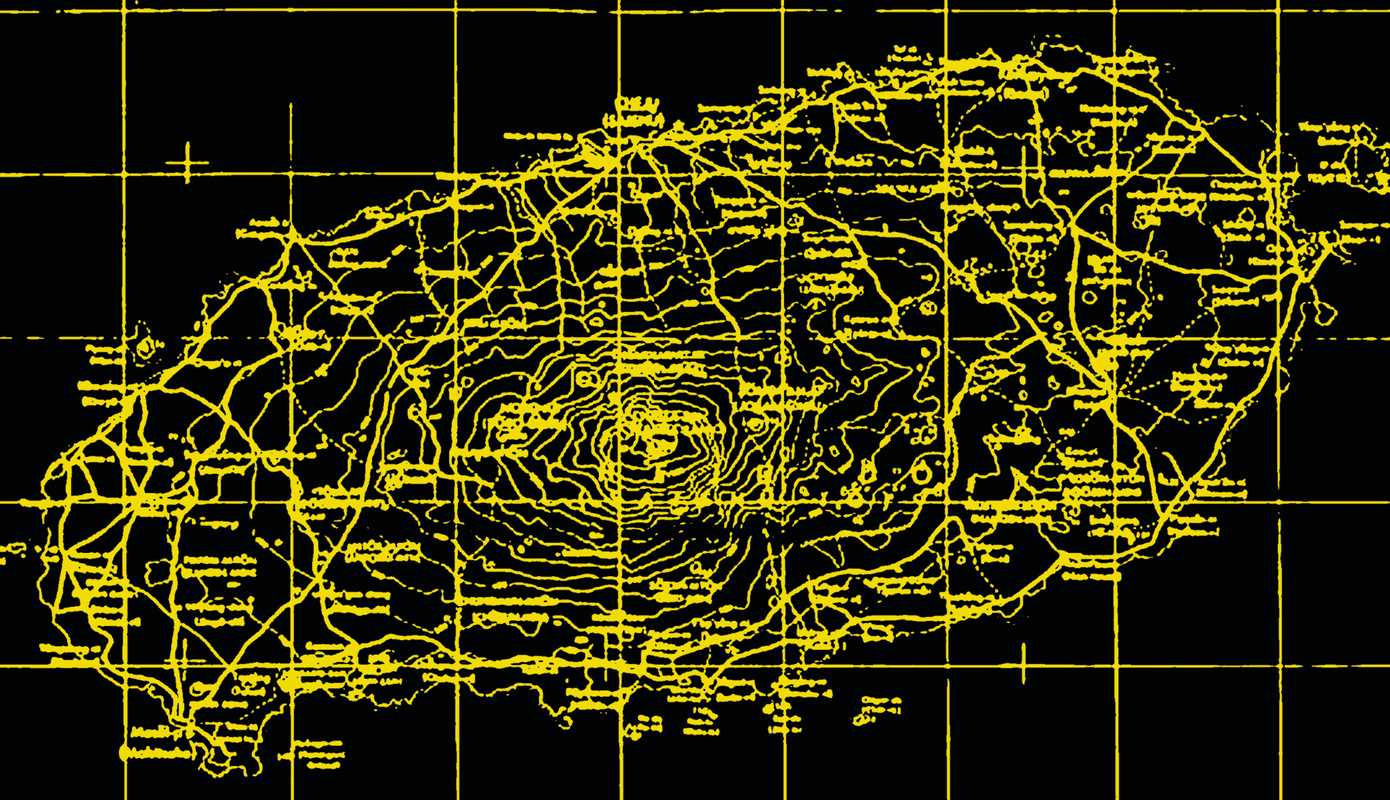

In a panic, US forces declared Jeju a “red island” and announced a suppression campaign of “armed rebels”, who they believed to be hiding in the mountains. The island was flooded with US and South Korean soldiers, whose method for identifying such rebels was to shoot anyone they found in or near an inland mountain. Families with missing members were identified as rebel sympathisers and gunned down. In the small village of Bukchon-ri, 300 people were killed in a single day. The slaughter only ended in 1954 – by then, 70% of the island’s villages had been razed to the ground, and 50% of married women were widowed.

For generations of South Korean children growing up after the Korean War, history textbooks mentioned this slaughter only as the “Jeju 4.3 Incident” (4.3 referring to the April 3rd uprising that became the official pretext for the armed forces’ invasion). When Jeju-born author Hyun Ki-young, whose family members were killed in the massacre, published a book about it in 1979, he was arrested and tortured for three days by the South Korean authorities and the book was banned for decades. Any public mention of what really happened was forbidden. How do you mourn when the shape and form of your loss is violently suppressed?

It was only in 1989 that the first open commemoration of Jeju 4.3 was held at Jeju University. 500 students gathered in a mass protest and burned effigies of the South Korean and US presidents. But more explosive was the student newspaper which finally put words to an unnameable incident: “Jeju 4.3 was not a left vs right struggle, but the lonely struggle of 300,000 islanders resisting violent oppression.” They called it the “Jeju Resistance”, and later, the “Jeju Massacre”.

Solidarity, so often thought of as the horizontal links between the varied causes of a single era, can also reach through time: to our elders and to our unborn descendants

Thus began the movement within a movement. Or perhaps it was just the continuation of the original. Young students, local civilians and survivors of the massacre (the youngest now into their 50s and 60s) joined in a dogged campaign that persevered at the heels of an ignorant mainland population. They extracted pledges from the island’s politicians to demand a truth commission and reparations from the central government way north in Seoul. Local newspapers printed interviews with families and advertised fundraisers for the campaign.

In a country obsessed with moving forward – barely out of crippling post-war poverty, newly democratised after decades of military dictatorships – the Jeju activists demanded the most radical thing possible: a pause. A moment to step back, listen and examine the trauma of the country’s past.

They did it: in 2000 a truth commission was created, led by human rights lawyer Park Won-soon (now Mayor of Seoul). It worked for three years and published a report that identified the perpetrators as the South Korean government, closely aided by the South Korean and US military. It led to president Roh Moo-hyun travelling to Jeju to issue the first official government apology in South Korean history.

Activists in Jeju made sure that the truth commission report contained provisions for the establishment of permanent memorial and research foundations, that would be in charge of the continued archiving of evidence – mass graves are still being uncovered, the most recent in 2008 next to the Jeju International Airport. The foundations manage reparations for survivors and family members, including art therapy and financial compensation. They are still demanding an official apology from the US; in 2017 a group of activists tried to hand an open letter to the US embassy in Seoul and were turned away.

The Jeju movement reclaimed the radical meaning behind truth and reconciliation: to shed a light on the past not as a way to close it or move on, but in order to better equip us for the struggle for our present and future. They show us that solidarity, so often thought of as the horizontal links between the varied causes of a single era, can also reach through time: to our elders and to our unborn descendants. To support the radical vision of those in our past allows us to create our own radical vision of the future. The thousands of Jeju islanders that protested in 1947, who rejected the election in 1948, teach us today that the borders we take for granted, the political systems we perceive to be immutable, can be challenged.

In Korean, the word solidarity, yeondae, is more often used as a verb than a noun. That verb gets closer to the heart of what solidarity should be: a moving, changing, responsive empathy to those causes around you. Solidarity in its static state can make our collective voice louder. But the action of solidarity often involves making ourselves more humble, more willing to listen to those around us and those who came before us. Listening to those voices can help us imagine something bigger than ourselves.

Footnote from the future (2024)

I vividly remember writing this piece. It was inspired by a visit to an exhibition in Seoul marking the 70th anniversary of the massacre, during a hot and sticky summer in 2018.

Not long before, nationwide protests had led to the peaceful impeachment and removal of corrupt president Park Geun-hye, daughter of former military dictator Park Chung-hee, under whose iron-fisted regime (1961-1979) activists campaigning for justice for Jeju 4.3 victims were arrested and tortured. The decades-long activism of the Jeju 4.3 movement had not only brought to light truths repressed by past dictators, but in the process contributed to weaving a civil society fabric strong enough to oust a corrupt president peacefully in the present. It was a hopeful time that seemed to prove that justice prevails through long-term, intergenerational activism.

Six years later, on a grey October day on the other side of the world, I am at another exhibition. The Jeju 4.3 archive is on display at the Brunswick Gallery in London, touring as part of a bid to register the entire archive with the Unesco Memory of the World project. From suppression in torture chambers under military dictatorships to the brink of Unesco recognition, the massacre is more visible than ever before, but today I find it hard to access that feeling of buoyant hope I had in 2018.

In 2022, the electorate of South Korea swung right and selected ultra-conservative Yoon Suk Yeol as president. His government supports controversial initiatives to erect memorials celebrating former dictator Rhee Syngman, who declared martial law over Jeju in 1948 and presided over the massacre. It has also cut funding for the Jeju 4.3 Trauma Center, which offers social healing for victims of state violence. Meanwhile, the US has still not acknowledged its part in the massacre, and continues to facilitate genocidal violence abroad with impunity. In an age where disinformation and historical denialism pervade our geopolitics, the visibility of Jeju 4.3 feels both precarious and insufficient.

On display in the exhibition is the novel that author Hyun Ki-young was imprisoned and tortured for writing in 1979: Aunt Suni, translated into English in 2012. Next to it sits Nobel literature laureate Han Kang’s forthcoming We Do Not Part (2025), also about Jeju 4.3. I am reminded that visibility is not easily gained, and we who live with its hard-won fruits should not take it for granted. Authors like Han can write about Jeju 4.3 for a global audience because our elders gave their lives to carve out space for us to speak.

But visibility alone does not guarantee progress; it simply builds us a stage from which we can be heard better. Battling through half a century of repression, it took Jeju 4.3 activists 55 years to finally win a presidential apology in 2003. It took another 18 years of campaigning after that for the first reparations to be paid to surviving victims and their families, and for retrials for those wrongfully convicted in former military courts to begin. The campaign to bring Jeju 4.3 to light was never an end goal in itself, but a midwife to material gains for justice. Many hope that increased international recognition to be gained from Unesco status will help pressure the US government to finally acknowledge its role in the massacre; this could be the first step towards the US contributing to reparations for the victims of its impunities abroad. It’s a long shot, but it could become a model for all those seeking justice for the harms caused by foreign interventionism and the domestic powers that collude with them.

On one of the gallery walls, there is a timeline of the massacre. Unfolding across two further walls – messy, sprawling and twice as long – is the timeline of the truth-seeking movement that followed. It does not show a linear journey that ends with the truth being brought to light, but a constant struggle to keep the truth in the light, despite the ever-looming shadows of denial and revisionism. In an age of fractured attention spans where even social justice movements appear to ride trends, Jeju 4.3 campaigners have remained steadfast in their simultaneous efforts to protect gains already made and to keep pushing for ambitions not yet achieved.

Hyun Ki-young has continued to write about the massacre for the last 45 years. His most recent novel, Jejudo Uda, was published in 2023, in the midst of the furore around the apologist memorials for Rhee Syngman. During the book’s press tour, he described how after his torture in 1978 he tried to stop writing about Jeju, but was plagued by the spirits of the victims in his dreams: “I wrote not because I had the courage to do so, but because the spirits of 4.3 ordered me to.” He is 83 years old now, and tired. “It may be too late but I would like to go back to pure literature, and write just a few words of it as I stand on the doorstep of the afterlife.”

It is surely our duty to continue shining the light in our struggle for liberation, so that Mr. Hyun and the spirits can rest.

Anthology brings together new and old stories to explore time: how we experience it, how it controls our lives, and how it can be reconfigured. For more stories about retrospection, inheritance, archiving, rhythm, pacing and change, order your copy now.

.png)