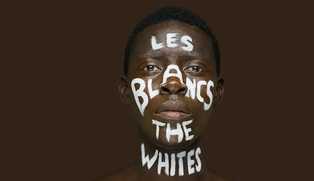

The fate of millions of people – indeed the future of the black community itself – may depend on the willingness of those who care about racial justice to re-examine their basic assumptions about the role of the criminal justice system in our society.” Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness

The United States of America incarcerates more of its citizens than any other country in the world. The Sentencing Project tells us that over 60% of those incarcerated in the United States are people of colour. Michelle Alexander encouraged us to consider not only the nature of our “basic assumptions about the role of the criminal justice system” but, also, who exactly has both the willingness and the capacity to effect real change. Who would have guessed that it might be the role of an architect to take up Michelle Alexander’s call and design for systematic change? Deanna Van Buren, a designer working out of Oakland, California has for many years been committed to the project of not simply re-examining, but radically re-designing the spaces and mentalities behind a criminal justice system catastrophically failing its population — a population that we know is overwhelmingly derived from low-income communities of colour. Conversations surrounding judicial reform may, more often than not, be played out in the political realm, but Van Buren believes that change is as much as anything a question of (re-)design. She looks to Michelle Alexander’s words as a source of motivation and has dedicated herself to the challenge of disrupting and deconstructing the basic assumptions behind a purely punitive justice system and the very bricks and mortar that reinforce them. Brought up in rural-turned-suburban Virginia in the 1970s, Van Buren was raised to be mistrustful of the justice system from a very young age: “My parents were clear that I should stay out of the justice system at all costs because it was unfair and biased in particular for people of color.” Yet, Van Buren’s early career took her out of Virginia and out of any contact with the American criminal justice system as she worked in a more ‘conventional’ architectural tradition, designing residential and retail spaces across the globe. Even when engaged in a more commercial practice, Van Buren recognised the value in being thoughtful about the built environment:

What we know about architecture and everything in between is that the design of these places affects our health and well-being, both physiologically and psychologically. For example, the way architecture interacts with nature, light, sound, air, scent, texture and materiality can reduce our heart rate in minutes or make us sick. It is critical that we think about our built environment not just for ourselves, but for the health of the planet to which we are inter-connected.”

Increasingly frustrated, however, with the reality of a profession that did not seem to benefit society’s most under-served communities, Van Buren returned to America and turned to the neglected space that she believed to be in the most urgent need of re-design: America’s criminal justice system. Her advocacy for change has led to an all-out refusal to design for the criminal justice machine in its current incarnation, be that prisons, detention centres or courthouses, all of which she believes are “part of a relatively adversarial and toxic structure”. As a board member of Architects, Designers and Planners for Social Responsibility, she has lent her voice to the growing calls for the American Institute of Architects (AIA) to modify its Code of Ethics to preclude its members from participating in the design of spaces built for torture and killing (i.e. solitary confinement and execution chambers). Yet, it was exposure to the experience of Azim Khamisa and Ples Flex that firmly committed Van Buren to a career spent “disrupting the prison industrial complex as a system”. Further collaboration with social scientist Barb Toews culminated in the birth of design practice FOURM in 2010 and a dedication to direct campaigning for an alternative, restorative model of justice. Michelle Alexander says, “Nothing has contributed more to the systematic mass incarceration of people of colour in the United States than the War on Drugs.” As it stands, the legal and architectural frameworks of the American justice system provide a closed circuit that denies peace and reconciliation and instead perpetuates the so-called ‘war on drugs’, which barely masks the reality of an age-old war on bodies of colour. It is within the very buildings of America’s judicial spaces that Van Buren observes this truth daily:

I think the most striking legacies of slavery can be seen when I am working inside prisons or jails doing design studios. I am really tired of sitting in a room full of incarcerated men and seeing that the vast majority are of color. The 13th amendment of the constitution granted African Americans their freedom except in the case of those who had committed a crime. They could still be enslaved. When I am in those places it feels like slavery is still alive and well.”

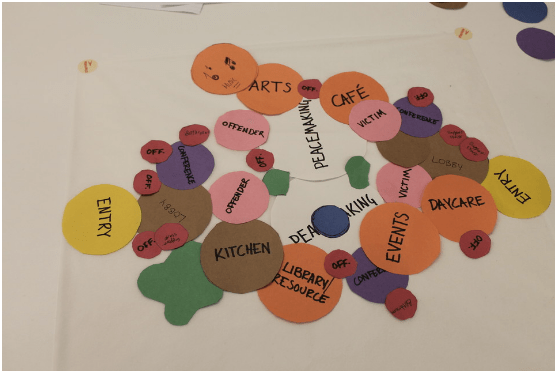

So, in a justice system currently designed to perpetuate war, how do you even begin to design for peace on a systematic scale? “I think peace is not a value of many countries in the world especially the U.S. I think we design for war and adversity all the time. We make decisions based on fear and psychological dysfunction that almost always leads to conflict and the architecture of conflict and punishment. Designing for peace systematically requires a complete shift in values, a position of empathy, and recovery from trauma.” Van Buren is not alone in calling for a systematic shift to restorative justice, a practice drawing on traditions from the Native American community that has already begun to gain global traction and influence. Yet, the inquiry into how you design for a fundamentally reparative system is a relatively novel one. She asks the question: what might reparative architecture look like? Grappling with the question of how to design “a new typology for social change” has taken Van Buren inside many of America’s prisons and the spaces and minds incarcerated within them. FOURM have conducted design workshops as part of the Inside Out Prison Exchange Program within criminal institutions, such as Graterford Maximum Security Prison (Pennsylvania) and these have privileged the experience and insight of incarcerated women and men in the redesign of judicial spaces. Van Buren has used the data collected from these ‘key-informant interviews’ to develop Designing Justice+Designing Spaces, a tool-kit which seeks to impact policy as well as “to solicit stakeholder input in the re-envisioning and re-appropriating of institutional space using restorative values and principles. Ultimately, this exemplar engages and solicits insight about the creation of environments based on love and forgiveness from those who stand the most to gain from them.” While striving, albeit ambitiously, to turn Oakland, California into a Restorative Justice City (an aim shared by Hull, England!), Van Buren has, in the meantime, focussed her attention on smaller, community-based restorative projects. The experience and data collected from inside prisons has shown her what major factors require consideration when designing a safe space for rehabilitation or peacemaking.

It must be a neutral space where people feel comfortable to go. It must also be easy to get to. It needs to feel safe physically and emotionally. It needs to reflect the culture of the people who will use the space and they should be involved in its design. Peacemaking centers need areas for reflection and privacy. In addition, it must have spaces for celebration particularly around food. Ideally, spaces for peacemaking will be integrated with and have access to nature. Some spaces for peacemaking are exclusively outside and why not? Our current criminal justice system requires severe opacity and physical control but with a different set up, goals and values, spaces for peacemaking can be exactly the opposite.”

Collaboration with the Center for Court Innovation in New York has involved FOURM in the design of a peacemaking room in Red Hook, Brooklyn for the Center’s pilot Near Westside Peacemaking Project. Three lengthy design workshops conducted with different community participants helped to create the first space and initiative that directly involves Native American peacemaking practices within the American criminal justice system. Following on from the success of Red Hook’s pilot programme, FOURM are collaborating with the Center’s Tribal Justice Exchange to build a second peacemaking center in Syracuse.

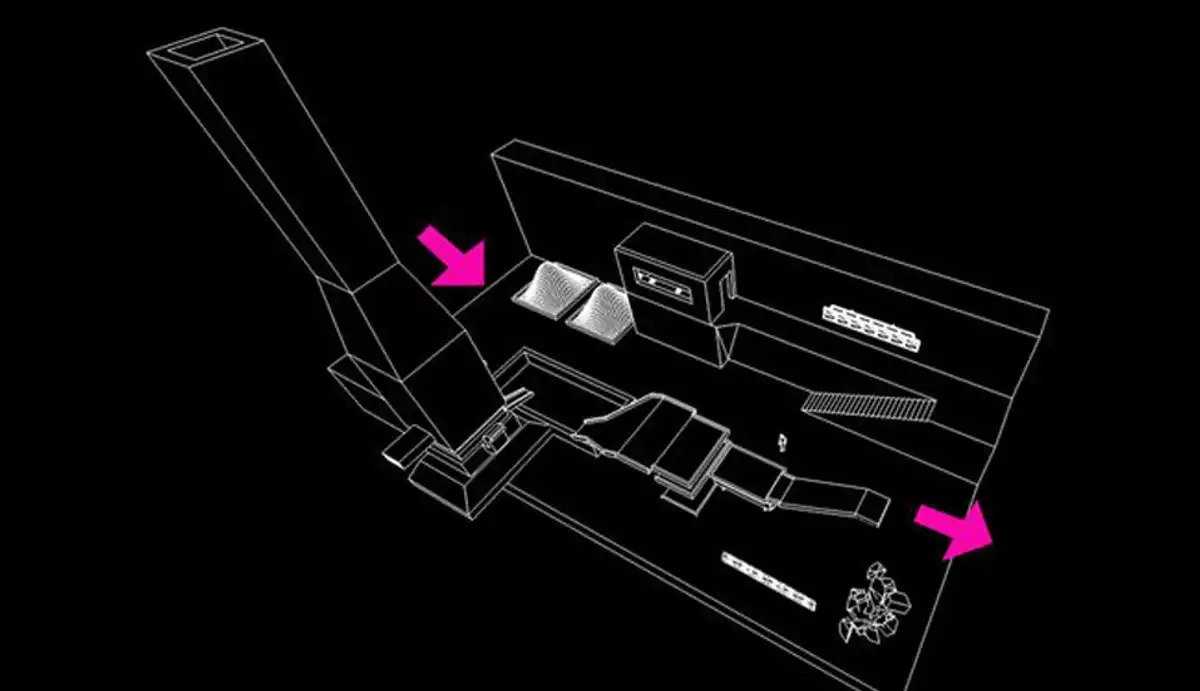

Syracuse peacemaking room render

With all this in mind, it becomes difficult to enclose Van Buren herself within the narrow role of the architect. She is at great pains to acknowledge “the capacity that architects have to transform anything, and everything. We shouldn’t limit ourselves in our capacity.” Indeed, Van Buren, and those working alongside her at FOURM, describe themselves as ‘wearing three hats’: the Artist, the Avatar and the Activist. Civic-mindedness and social inclusion are at the core of not only her activist practice, but all her projects; her design work on the video game The Witness and her upcoming artistic collaboration with producer Jim Lasko, The Field, demonstrate her conviction that art, both traditional and digital, must play a vital role in activism.

I see in criminal justice that a core issues on all sides are high levels of trauma. In my personal experience and with most of my favorite artists, I see art being used to support trauma healing at many scales. It can address the healing of historical legacies of violence in the case of Krzysztof Wodiczko’s Public Projection in Derry, mass social conflict like One Million Bones by Naomi Natale or current trauma events like the Philadelphia Mural Project’s work. In all mediums, art can be a doorway for people to access complex topics, themes and systems that need to be addressed in order to influence social change and our environments.”

Fitting then, that in 2015 Van Buren should have been awarded an Artist as Activist grant from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation in order to further her next project: a Pop-Up Resource Village for San Francisco’s most underserved communities. In partnership with the Five Keys Charter School and students from the Asian Neighbourhood Design’s Employment Training Center, Van Buren is in the process of re-purposing three San Francisco municipal buses, donated by the city, to provide urgently needed services to the formerly incarcerated and their communities at large. Community participation is key.

We know that greater connectivity and empathy between members of a community leads to reduced crime. By designing and building spaces for restorative programming […] we will be creating the new types of places we need to support a shift from mass incarceration. I also hope that the communities where we work will understand the power of design and the built environment, as well as their agency in making these places a reality.”

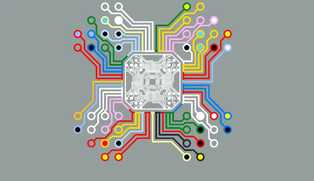

Two ‘School On Wheels’ sites, with classroom and library facilities, are in the initial stages of construction. They will be accompanied by a third mobile shelter, providing refuge for vulnerable inmates released from institutions at night. Yet this is just the beginning; the vision is to create an entire Pop-up Resource Village, let’s remember! Recently awarded a Google Impact Challenge Grant, Van Buren is now starting to make this vision a reality.

Van Buren’s multi-disciplinary and multi-coloured approach to radical redesign seems to be the exact antithesis and the perfect antidote to systems that see things in black and white and people in enclosed spaces. Van Buren chooses the words of Zulu healer, Credo Mutwa, to best encapsulate her belief about the power of open, circular space: “Lines tend to create separation and aggression; circles create oneness, unity and peace.” It is important for us then to come full-circle to the words of Michelle Alexander: “We could choose to be a nation that extends care, compassion, and concern to those who are locked up and locked out or headed for prison before they are old enough to vote.” Deanna has chosen to do just that. She tells me that she returns over and over again to the words of Dr. Cornel West in her practice: “Justice is what love looks like in public”. What is clear is that Deanna Van Buren is helping America to redesign its heart.