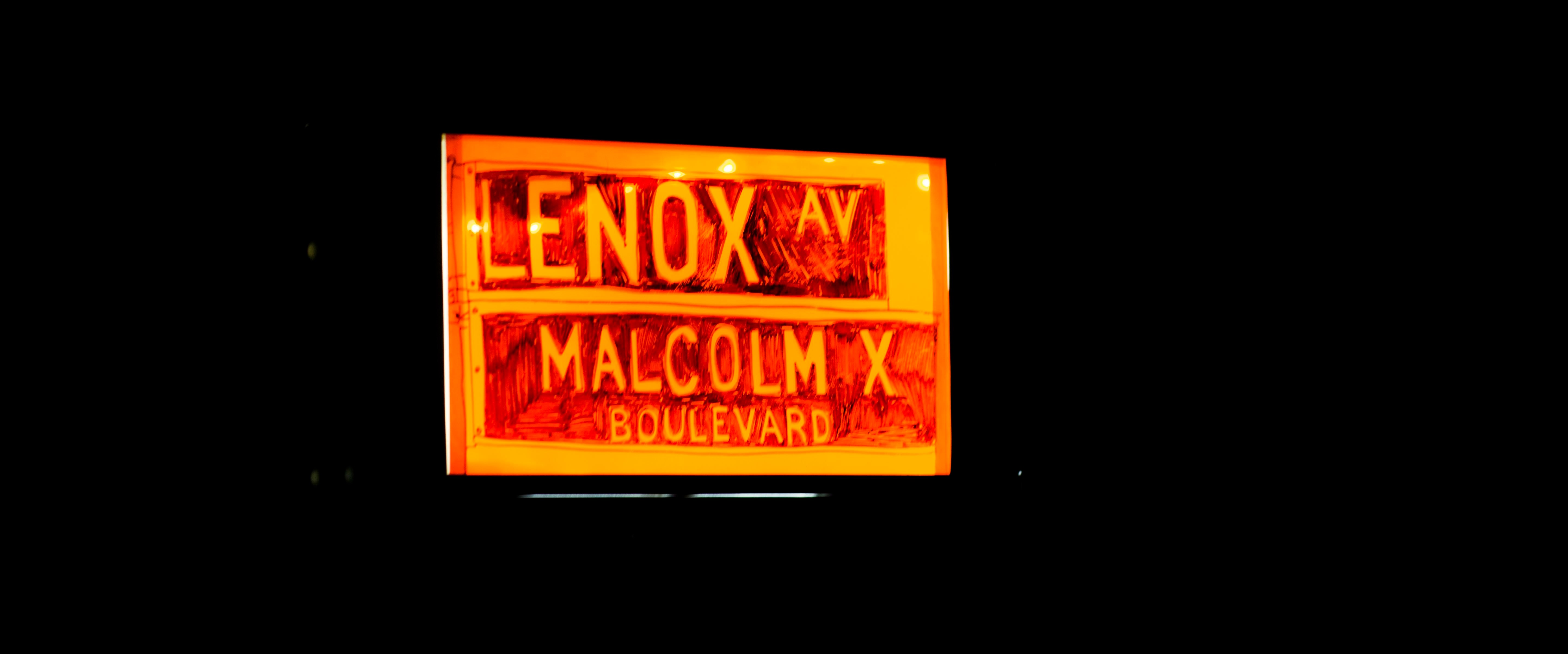

The Year of the Rooster Monk, currently on at the Pleasance Theatre, is a play full of millennial threads: gentrification, unemployment, parental relationships, and rose-tinted recollections of the nineties. Starring Giselle Gant, whose wonderful comic timing and creative storytelling help tie these threads together, the play boldly attempts to present a Black woman’s multilayered relationships to her Harlem home, the ghosts it holds, and herself. I enjoyed the range of practices Gant and her director Nathalie Adlam brought to the show; there was Giselle the poet, Giselle the stand up comedian, Giselle the physical theatre artist. A talented performer, she was a joy to watch. But The Year of the Rooster Monk at times gives into a trope millennials are often accused of exhibiting: too many options, not many decisions. The play’s ambition to stay true to the complex interconnectedness of issues millennials face is important – we are priced out of the neighbourhoods we grew up in, which affects our sense of stability, which in turn has the potential to further shape our economic success. But I was left wondering what exactly we are meant to take away about Giselle by the end of the play. I don’t think this is a story that needs a neat and tidy ending, and its creators know that. Perhaps a greater focus on Giselle’s relationship with her mother, in bringing together the past, the present and the future, would leave the audience with a better idea of why Giselle’s journey through time and space is one that we are also on. Having debuted earlier this year at Vaults Festival, The Year of the Rooster Monk went through a short development process before coming back for this run at the Pleasance. I’m excited to see if and how the creative team choose to develop it further. Before seeing the show, I sat down with Giselle and her director Nathalie Adlam, to talk about the play and their process. Below is our lightly edited conversation. I was trying to figure out the root of the title. I’m assuming it’s to do with Chinese New Year? Nathalie Adlam: Yes, when we were coming up with a title, Trump was in. It was the Year of the Rooster, and the Year of the Monkey had preceded it. We liked the idea of playing around with this awkward fusion, this threshold of time. Giselle Gant: Because there is a period, which I think is about a month, where the Gregorian calendar and the Chinese calendar roll together, so that one month is very weird kind of time. Nathalie: And Trump got inaugurated in January. Giselle: Yeah, that was right in that gap. It’s in that landscape where everything feels turbulent. Is that the tone of the piece? Nathalie: Exactly. Ill omens are a dime a dozen, and I think that’s not only in your personal life where you have your own meltdowns, but also in the outside world where everything seems to line up, too. That is our backdrop. Can you tell me a bit about the play’s development? Nathalie: We did an elaborate scratch at Vault and we’ve tried to build on what worked there. We only had three weeks the first time so we were under pressure, and thinking about devised shows, they just take longer than that. We realised that these slightly surreal, magical realist elements of this piece just popped out more, and resonated with people. The mention of magical realism excites me. I’ve read everything I can on this, and I am still not quite sure what to expect. Giselle: That’s part of the magic. Between us, we’re mad people, so it’s just really a mad show, there’s a little bit of everything. And it’s set in New York. Giselle: Yes, it’s set in Harlem. I’m a Harlem-ite. This piece really is a love letter to Harlem, and becoming increasingly so. To a Harlem that’s changing… Giselle: Yeah, and though we say this is a one woman show, there are a lot of characters in this piece. And Harlem is definitely one of those characters. What are some of the influences behind this show? Nathalie: The starting point for [Giselle], which I was interested in but didn’t perhaps understand, was something she said to me: ‘there’s this idea of black girl magic and I don’t really know what mine is.’ Giselle: Right. I know the woman who coined the phrase ‘black girl magic’. And so following her journey with that, it became a movement, a great empowerment movement. You can see all these wonderful beautiful women that have black girl magic: Michelle Obama Michelle Obama has black girl magic, you can go to Afropunk and see all the black girl magic there, but then for the regular girls: what is ours? How do we tap into it? It feels a bit like an ethereal thing. Giselle: It does, and not tangible. And me, I like to think of things literally. If black girl magic is literal magic, then what is it? So [with the play] it’s sort of afro-futurist as well, drawing on the past to get through the present, to shoot into the future. It makes me think of the internet and the way these things are all connected. How much does this fast, everything-is-changing-all-the-time, digital age feature in this piece? Nathalie: Loads, and that’s partly because we stand on completely different sides of the millennial experience of the digital age. I’m on that early cusp, and so I have always found the evolution of social media terrifying, alienating. Whereas [Giselle] embraces it more. But we were interested in this generation who sit on the threshold. And we wanted to riff on that [cusp]. In theatre it’s being incorporated in some ways, but not necessarily with the remembrance of this ghostly digital past. Giselle: We use ghosts in a four-fold way. We talk about the movie Ghost (I used to love that film). We talk about ghosts of the past, the ghost of an apartment, and the ghost of who you were versus who you are now. Nathalie: There’s nothing stable about our identities in this fast-moving social media culture, and I think that’s how one feels. Giselle: [Nathalie] doesn’t believe in ghosts and I do wholeheartedly. Who should come out and see this play? Giselle: Honestly, us millennials. We’re in an age where the economy is very hard, we are under a lot of pressure, our parents say that we should be further along than we are and we’re somehow not, and we’re in debt. We’re also very isolated. How do we come out of that? How do we find our black girl magic and step out into the world and just trust that we got this? I think this is really the story of a woman trying to find that for herself. Trying to step out and believe it will be alright. The Year of the Rooster Monk is on at the Pleasance Theatre until the 3rd June 2018. You can buy tickets here.

Cultivating the everyday #BlackGirlMagic: The Year of the Rooster Monk at the Pleasance Theatre

Nkenna Akunna sits down with Giselle Gant and Nathalie Adlam to chat about The Year of the Rooster Monk at the Pleasance Theatre.